|

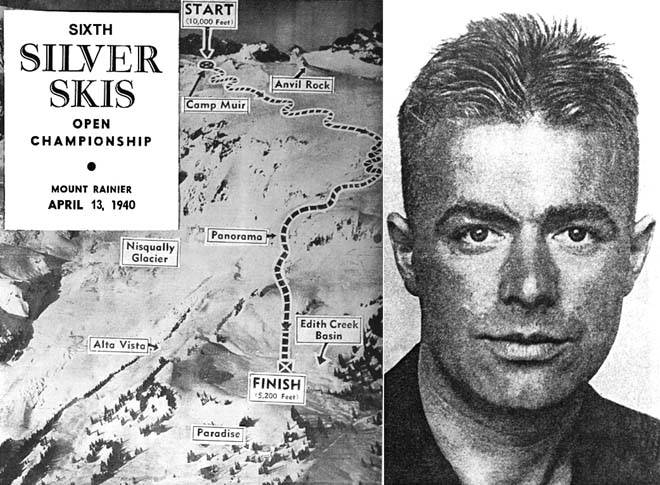

| Left: The Silver Skis course on Mount Rainier. Right: Sigurd Hall (from the American Ski Annual, 1940). |

|

A

band of fog draped the Silver Skis course on Mount Rainier as

racer Sigurd Hall pushed off from the start. The date was April

13, 1940. Visibility near Anvil Rock was so poor that several

competitors ahead of him declined to race. "The course was

described as hard, icy and exceedingly fast in the opening

stretches," journalist Fred McNeil later wrote in the

American Ski Annual,

"and tremendous speed was possible." Hall, born Sigurd Hoel in

Norway in 1910, was the top-ranked ski racer in the Pacific

Northwest. He was one of the top downhillers in America.

Just below Anvil Rock, near a formation known as Little Africa, Hall strayed off the course to the skier's left and sped toward a wedge of rocks that extended out into the Muir Snowfield. "His skis were heard banging along at speed," wrote McNeil, "indicating he was 'wide open.'" At the last moment, Hall saw the danger and tried to veer to the right. His skis shattered on some isolated rocks and he hurtled head-first into the wedge. "Such was his speed," wrote McNeil," that he was thrown entirely across this wedge and into the snow beyond." A spectator trained in first-aid hurried to him, but apparently he died instantly. Thanks to Dee Molenaar's book, The Challenge of Rainier, the name of Sigurd Hall has lingered in the memory of Northwest skiers and mountaineers. Yet few appreciate his story. As a competitor, Hall was the top skier in the Northwest at the time of his death. He was also the most accomplished ski mountaineer in the region before World War II. Less than a year before his death in the Silver Skis race, Hall made the first ski ascent of Mount Rainier, completing his quest to ascend or descend on skis every Cascade volcano from Mount Baker to Mount Hood. He also made pioneering ski trips to Eldorado Peak, Ruth Mountain, North Star Mountain, Mount Daniel, the Goat Rocks and other remote Cascade peaks. As the top practitioner in both ski racing and ski mountaineering (simultaneously!), Sigurd Hall occupied a place in Northwest skiing history that may never be filled again. War engulfed Norway within days of Hall's death in the Silver Skis race. Mail to the Hoel farm in the Sunndal Valley was disrupted. News of Sigurd's death reached the family, but the details were sketchy. As the oldest son, Sigurd would have inherited the farm if he had returned to Norway. The property went to his younger brother instead, and the memory of Sigurd Hoel passed into family legend. |

|

| L-R: Gunnar Hoel, Jon Rekdal, Odd Hals, Endre Hals, and Jeff Earle at Moon Rocks, the approximate site of Sigurd Hall's crash in April 1940. |

|

Born in Norway shortly after World War II, Odd Hals grew up with

the legend of his uncle Sigurd Hall. An outstanding athlete

himself, Odd was puzzled by some aspects of the story. For over

50 years, the Hoel family legend said that Sigurd had won the

Silver Skis. The accident, it was said, took place after the

race, during a "lap of honor." This never made sense to Odd, and

his curiosity about the circumstances of his uncle's death grew

over the years. Odd's cousin Gunnar Rekdal shared his curiosity.

Gunnar had inherited the family farm and in keeping with

tradition had changed his last name to Hoel. Together with

Gunnar's brother Kristen, they nursed the idea of coming to

America and visiting Mount Rainier.

This smoldering idea caught fire in 2002, when Judy Earle, a Seattle-area cousin of the Hoel family, traveled with her husband, Dick, to Norway to revisit her Scandinavian heritage. Judy learned about the legendary Sigurd Hall, and upon returning to Seattle, began trying to find out more about him. A search on the internet led to the Alpenglow Ski Mountaineering History Project. A brief e-mail through the project website led to me. I mailed Judy photos, articles, and 16-mm movies of Sigurd Hall, which she immediately forwarded to the family in Norway. Just two months after our first contact, Judy told me that one of Sigurd's sisters (Gunnar's mother) had passed away in Norway at age 90. A month before her death, Gunnar showed her the films of her brother skiing in the Cascades in the 1930s. She said that it was like bringing Sigurd back to life again, after more than 60 years. In Norway, planning for the journey to America continued. During the winter of 2005, Judy informed me that Gunnar, Odd, and Odd's son Endre had scheduled a guided climb of Mount Rainier on July 22-24, 2006. Judy's sons Jeff and Doug Earle planned to join them, and Gunnar's nephew Jon Rekdal made arrangements to fly out from New York to join the expedition as well. At the last minute, Doug Earle had to withdraw from the climb. I took his place in the party, and we converged in Ashford on Saturday, July 22, for a one-day climbing school conducted by Rainier Mountaineering, Inc. (RMI). On Sunday, July 23, Gunnar, Odd, Endre, Jon, Jeff and I began the hike from Paradise to Camp Muir with RMI guides Mike Horst, Corey Raivio, Andreas Marin and two other clients. We made a special stop near Anvil Rock, at the formation now known as Moon Rocks. Based on written accounts and information provided by Karl Stingl, a former Silver Skis racer who knew Sigurd Hall, we concluded that this was the approximate location of Hall's death. (See photo above.) It was impossible to exactly match the terrain described in Fred McNeil's 1940 American Ski Annual article, but we figured this was probably due to melting of the Muir Snowfield. It is likely that more rock is exposed today than in April 1940. We felt satisfied that we'd found the right area even if we couldn't pinpoint the accident location precisely. |

|

| Sunrise near 13,500 feet during the climb of Mount Rainier. |

|

Due to the hot weather, we started our climb of the Disappointment Cleaver

route very early on Monday, July 24, leaving Camp Muir around midnight.

Stars filled the moonless sky. Our necks craned skyward as we watched the

first rope teams, the lights of their headlamps seemingly suspended in air,

snaking their way toward the summit. One of our party had been fighting a

stomach sickness for several days. At "High Break" (13,500 feet) the

guides decided it would be best for him to stop. They skillfully made him

comfortable in a sleeping bag on a quickly-constructed snow platform. The

rest of our party climbed to the crater, and several continued to the

register book at Columbia Crest.

Odd produced a small banner bearing the Norwegian colors, which we signed in Sigurd Hall's memory. I scattered the last of the ashes I had been keeping since the funerals of my brother Carl and mother, Ingrid, the previous winter. With photos and memories secured, we made our way back down the mountain, down to Camp Muir, down to Paradise. We were greeted near Alta Vista by Judy Earle and her sister, Odd's sister Gunvor and her family, and more members of the extended Hoel clan. We eventually gathered for dinner at Alexander's Inn near Ashford--all seventeen of us, including Gunnar's sister Olaug from Sweden. I asked Judy whether the family often gathered like this, and she said it had never happened before. She passed out lyrics of a song she wrote for the occasion, and we joined together to sing about Sigurd Hall and his home in Norway. So ended one of the most memorable climbs of my life. The Orchard Blooms At Hoel For a more detailed story of Sigurd Hall's life, see this 2016 paper (40Mb+) by John Lundin, a volunteer with the Washington State Ski and Snowboard Museum. The paper was researched with extensive help from Norwegian relatives of Sigurd Hall, especially his nephew Kristen Rekdal. |

The Alpenglow Gallery