|

|

|

|

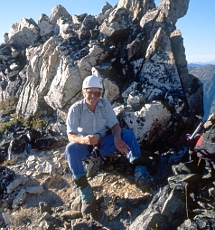

| Silas Wild on Thunder Peak's East Ridge, September 1998. Mount Goode is in the distance. | |

|

Climbing down

from a new route on Thunder Peak in the North Cascades, Silas Wild and I

descended the final moraine at dusk. Silas was a few yards ahead of me,

angling toward the valley bottom. A few more paces would put us on flat

snow, not far from our camp.

The rock that triggered the avalanche was about as large as a TV set and weighed well over a hundred pounds. When Silas stepped on it, the stone rolled, starting a chain reaction of boulders tumbling underfoot and above him. Silas fell into an avalanche of pounding, grinding blocks. I froze, afraid I was watching him being crushed. "Silas!" I shouted as the crashing came to a stop. "Oh God," he moaned. "Help me!" I scrambled down and found him on his back, his legs and right arm buried by stones and a suitcase sized rock lying on his chest. "I can't breathe!" he gasped. I strained to move the boulder, relieving some of the pressure, but unable to lift it clear. "Get it off of me!" he cried. Silas pushed with his free arm and together we shifted the rock to the side. "My arm!" he cried. I began unstacking the heavy blocks that trapped his right arm. I looked anxiously at the boulders poised above me, afraid that too much excavating might bring them down upon us. My mind raced wondering if I could move the huge blocks that pinned his legs.

Once his right arm was free, Silas breathed a little easier. "Loosen my pack straps," he said. "I might be able to work free." Miraculously, Silas wriggled his legs out from under the blocks. As they came to rest, the boulders had created a pocket that trapped his legs without crushing them. Silas rocked back and forth, moaning in pain and pleading for an explanation of what he had done wrong. His right arm was swelling badly. A gash on his shin oozed blood. But he had no other cuts or broken bones, just bruises and aches everywhere. While Silas bemoaned his bad luck, I marveled at how lucky he had been. After we talked about our options, Silas managed to stand and hobble painfully across the snow. There was a good bivouac site a few hundred feet away with flat ground and running water. In the twilight I fetched our overnight gear from our previous night's camp. We bandaged Silas's leg and got him into his sleeping bag. I offered to hike out for help the next morning. My mind was spinning as I settled in for a fitful night's sleep.

Thunder Peak is an 8800 foot satellite of Mount Logan in the North Cascades. It is rarely climbed; most Northwest mountaineers have probably never heard of it. Yet its 2000 foot east ridge is reminiscent of North Cascade classics like the west ridge of Eldorado Peak or the northeast buttress of Mount Goode. I first noticed the ridge in 1982, during a ski ascent of Logan. I mused idly about it for years before realizing that it might be approachable without a bushwack. On Labor Day weekend in 1998, Silas and I hiked over Easy Pass, down the Fisher Creek trail and up a steep forest to a mile high lake north of Mount Logan. This lake is the normal basecamp for Logan's Banded Glacier route. It had been a dry year in the Cascades and the holiday weekend, usually a magnet for rain, promised beautiful weather. On September 6, from our camp above the lake, we crossed a 7040 foot col ("Birthday Pass") that was the key to accessing the route. We traversed below a pocket glacier, scrambled the first few hundred feet of the ridge, then belayed three pitches to a tower at 7500 feet. The adjacent 100 foot notch was steep walled and intimidating. We wondered if we could climb back out once we committed to the rappel. I volunteered to take a closer look, figuring that I could prusik back up the tower if the other side of the notch didn't go.

While searching for a rappel anchor, we noticed rope fibers, evidence of a previous climbing party. So, we weren't the first climbers lured by the ridge! Did the earlier party retreat from here or finish the climb? We never found any other evidence, so the answer is a mystery. The notch looked passable once I got into it, so I called Silas down. Climbing out was the crux of the route. I reached across the narrowest part of the notch to some incut holds, swung over, hand traversed left, then worked up and back right. I found a key chock placement and prepared to aid off it, then discovered a layback move that got me past the bulge. Following the pitch, Silas thought it was probably not harder than 5.7. We traversed left to the crest and a straightforward chimney appeared, leading through a headwall that had looked formidable from below. From there to the second notch at 8000 feet the climbing was mostly low class 5 on enjoyable rock. The shadowed north wall of Mount Goode and the wildly broken Douglas Glacier made the setting magnificent. Behind us, the meadows of Easy Pass, Spectacular Ridge and the Arriva-Black group showed the first hint of autumn color. The second notch had a short rappel and a rotten gully, but the rock improved above it. The climbing gradually eased and we reached the summit about ten hours from camp. Our view from the top expanded to include Mount Baker, the Picket Range and the icefields of Eldorado. Mount Logan's summit cast afternoon shadows on the Banded Glacier spread before us. We noted icebergs floating in the lake at the glacier's foot.

We descended the regular route down the north ridge, then took a shortcut back to camp by rappeling off the divide a quarter mile southeast of Christmas Tree col. From there, the going was easy until we came to a cliff band above a steep moraine. Tired after the long day, we had to concentrate to get down these final obstacles safely. In hindsight, maybe we dropped our guard just a little on the last thirty feet of moraine. Thirty feet was all it took for the avalanche to catch Silas and trap him. I shudder when I think of the consequences of being caught like that alone. The rock slide forced me to think differently about moraines. In the past my partners and I have usually moved together on moraines to avoid kicking stones down on each other. But now I think you need to treat unstable moraines like potential avalanche slopes. That means keeping far enough apart that only one climber can be caught at a time. On the morning of the third day, Silas felt better and thought he could hike out. We loaded the heavy gear into one pack, which I carried, and put sleeping bags, bivi sack, food and a headlamp in the other pack for him to carry. Since his right arm was useless, I lowered him with the rope a few times down the steep, cliffy forest. After we reached the Fisher Creek trail, I hiked ahead to Colonial campground, thirteen miles away.

I wondered during the long hike whether it was right to leave him alone. Silas is a North Cascades veteran, having spent more time in rugged corners like the Picket Range than almost anyone else. He has climbed in Alaska and made seven trips to Patagonia, which he wryly calls "the advanced backpacker's final exam." Yet despite his experience, I worried about him, since he was hurting and weak and couldn't even tie his boots by himself. I suspected he'd have to spend another night on the trail alone. At dawn on the fourth day, two park rangers joined me at the Thunder Creek trailhead to look for him. We found Silas just an hour up the trail still moving slowly and steadily under his own power. Back in Seattle the doctors reported a broken wrist, deep bruises, and a cut on his shin that should heal without stitches. Despite the accident, Silas and I felt it had been a good trip. The avalanche reminded us of how much we depend on each other in the mountains. We coped well enough to get ourselves home. For me, the climb was very satisfying, transforming years of daydreaming into one memorable day. I discovered that there are still corners of the Cascades where the feeling of exploration is strong. That feeling was unmistakable, a powerful mixture of anticipation and doubt, as we reached Birthday Pass and got our first close-up view of the ridge, etched against the morning sky. --Lowell Skoog

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Alpenglow Gallery |