|

he

following is a story of two forays to Logan that tested my

endurance. The first is a tale of acquainting myself with my physical limits

of climbing in a 24-hour day. I left in the evening of July 31st, expecting

to cover just a few miles. Instead I carried a micro bivy for 15 miles

that Monday before collapsing in a nervous sleep. The ranger lady had me

freaked out

about

bears, and scat was everywhere, proving her point. he

following is a story of two forays to Logan that tested my

endurance. The first is a tale of acquainting myself with my physical limits

of climbing in a 24-hour day. I left in the evening of July 31st, expecting

to cover just a few miles. Instead I carried a micro bivy for 15 miles

that Monday before collapsing in a nervous sleep. The ranger lady had me

freaked out

about

bears, and scat was everywhere, proving her point.

|

|

|

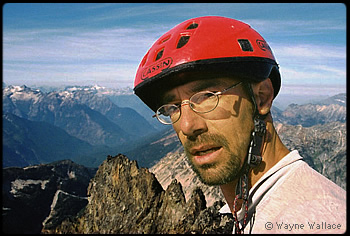

View down the NW Ridge of Logan. © Wayne

Wallace. Enlarge |

|

|

After dreaming of collapsing bridges, I found I had overslept to the “late” hour

of 4:30 in the morning. I still had many miles to go and much elevation to

gain. The bushes were loaded with water from the previous day’s rain.

I tried to knock them dry with a stick, but after a few miles, I resigned

myself to being soaked. The way had heavy debris and was hard to follow.

The climb would have gone more quickly, but a foggy whiteout got me miles

off route. I wished

for any type of a view, but the veil was thick and I felt lucky to have made

it at all.

Logan seemed a remote and seldom-visited mountain; I was surprised

to find myself the apparent first to summit in the 2003 season. The summit

brings another realization. The problem with long approaches is that one

must hike an equally long way out.

Not

excited

about this fact, I took a shortcut on

the way down. This “shortcut” proved to be insane but manageable

with only creative down climbing involved (no rappels).

I didn’t expect to try Mt. Logan in a day until

I glanced at my watch on the way out. (With a little planning, a much shorter

round trip time is quite possible.) Now hot on this idea, I started moving

very fast and at times was flat out running. Never having pushed myself to

that extreme, now witnessing my body break down was interesting. Of course

I had the usual foot pain, but new and terrible things were occurring

too. My quads were actually going numb, and I didn’t know what to make

of the horrendous pelvic pain. It left me glad that males cannot get pregnant.

October came in with nice weather. I was again between jobs and without a

mid-week partner. Feeling restless for adventure, I began looking over topo

maps for something new. My eyes couldn’t believe what I saw on Mt.

Logan: The Northwest Ridge looked to be the biggest and longest ridge feature

in the whole North Cascades. Huge serrated gendarmes soared all along its

mile-long spine. Alan Kearney made an ascent up a face below its north flank

but never even got to the crest of the ridge itself. It truly appeared to

be untouched, and for good reason! Little did I know that I was about to

be tested to my core physically, as on my

first

trip

to Logan, but also mentally.

In my many decades of climbing, I have found no greater reward than going

alone into the unknown. It seems one must really enjoy climbing for climbing’s

sake to choose this way. Remove the comfort and camaraderie of having a partner,

and what remains is just you against yourself and this big scary goal. An

entirely different atmosphere is created. Confidence is the only currency

accepted here. Leave your credit card at home.

|

|

|

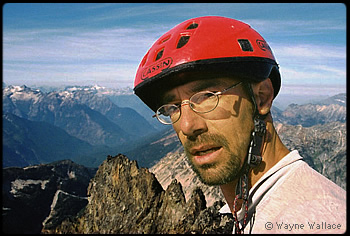

Back along the NW Ridge of Logan. © Wayne

Wallace. Enlarge |

|

|

Not willing to let technical difficulties hold me back, I slogged in with

full climbing gear, including a rope, full rack, Soloist, hammer,

and even pitons. Because it was October, I added a sleeping bag, stove, and

bivy

sack. With all of this weight, I was hoping to be able to return to a camp

at the base where I could leave the bivy gear, but I could not even figure

out how to get into the valley to reach the base of the ridge itself! This

gateway to the ridge was the most protected valley I had ever seen,

rimmed on all sides by large cliffs. I put away the topo map, hoping for

a bit of luck.

Heading up the now familiar Thunder Creek was still a beautiful journey.

I decided to leave the trail at Junction Camp, fully knowing a

major bushwhack was ahead. I went light on the water, and was parched when

I reached the ridge, west above the Logan Creek valley. Seeing a lake 400

feet

below did not help; a cliff separated me from its quenching

shores. Further up the ’whack I saw another more reachable lake that

led me to water of course, but also deer tracks that led from the lake

toward the Logan valley. Curious to see where the tracks went, I followed

them to where I could overlook a bizarre triangular fracture in the valley

wall. It seemed the whole side of the valley, for a couple of miles, had

actually collapsed to form two micro-valleys. Here was my luck in accessing

the route:

One fracture led down to the valley proper, and the other led me right up

into the beautiful Logan Creek valley where I could camp and then gain the

base

of the Northwest Ridge. This feature I called “The Wrinkle in Time.” I

found the two valleys stunning despite the ubiquity of bear scat.

I decided a plan to climb and return to camp was impossible, so I carried

a heavy load onto the ridge.

This

Northwest Ridge was the longest of any ridge that I had ever seen in the

lower 48 states. The 4th-class climbing went on and on for hours until rappelling

became necessary

down

the backsides of many of its gendarmes. These pinnacles showed no signs of

human travel as I wrapped sling after sling over them. The pinnacles got

larger and more difficult as I went along. I was growing concerned as less

and less rope was reaching the bottom of each rappel. The last two gendarmes

proved to be the most stressful in terms of difficulty and route finding.

Well past the point of no return now, I was exhausted

and scared shitless — a bad combination. My thoughts were occupied with escape

and survival bordering on desperation. There simply had to be a way up the

thing,

but

the rock was

somewhat loose and offered almost no protection even if I felt the need for

the rope. My hands where jarred from all the hours of thumping on the questionable

holds, and my nerves were shattered when I slipped while down climbing. I

later discovered that I had broken ribs when I slammed my chest into the

rock from the slip.

After 8+ hours of endless climbing I reached the wafer-thin final ridge.

It relented to better rock but overhung slightly and was unbelievably exposed.

Mantling onto the summit ridge brought me to a true knife-edge ridge of shattered

rock and missing blocks. Negotiating it took great care. The summit

meant more to me this 2nd time; I was now released from the grave

danger of the free solo of the very long and stressful climb. I cannot describe

the relief this mountaintop now provided. It felt as

if

the peak

itself had a foot on my heart and my task was to struggle free of its

weight. This Logan rematch left me feeling a special bond

with its lonely mass of rock and snow.

The way out was hindered by my decision not to take crampons. I sketched

along vast glaciers in my tennis shoes worrying about taking “the great

slide.” Twenty miles of trail did their best to work out the remainder

of my reserves on a hike split by a sleepover at the old mine. The

descent was

demanding yet closed a very satisfying trip. I hope you, the reader, can

find adventure and joy in these wild places; perhaps Logan is waiting for

your

feet as well.

Here’s to your trip. Cheers!

|

|

| summary |

| |

|

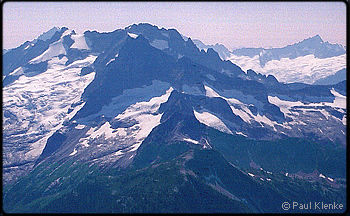

| Mt Logan |

|

North Cascades National Park

Elevation 9,087 feet

|

|

| Itinerary |

|

July 31 to Aug 1, 2003

24-hour climb of the Banded Glacier. |

|

October 2003

First ascent, solo, of Logan’s complete NW Ridge. |

| |

|

|