| Mission | Submission Guidelines | Editorial Team |

| Issue 2 | Archive |

| Wolf Bauer | ||

| Part 4 |

|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

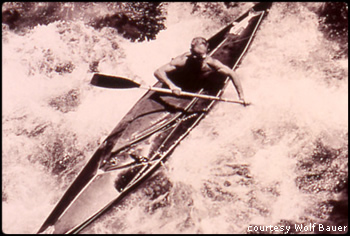

Harry Higman, Wolf’s old scoutmaster, introduced Wolf to foldboating on the lower rivers of Puget Sound after World War II. Foldboating was developed in southern Germany in the 1920s, and Wolf recalled seeing foldboat clubs on the Inn River in Bavaria as a schoolboy. The original “faltboot” was conceived by Hans Klepper of Germany and made of rubberized canvas with a wood frame. It was designed to be folded up and carried as train baggage or towed behind a bicycle. In the 1960s, Wolf designed fiberglass kayaks after it became clear that a folding boat was no longer needed.

During the 1940s and 1950s, Wolf and friends such as Herb Flatow and Hubert Schwartz made first descents of most of the major rivers in Washington. In a conversation over forty years later with Beth Geiger, Herb Flatow recalled, “We’d drive along some river and think, well we could probably run that, so we’d just go. We ran a lot of little rivers nobody probably even bothers with now.” A milestone for the group came in the mid-1950s when they made the first descent of Boulder Drop, a complex section of whitewater on the Skykomish River near Index, Washington. As usual, Wolf was in charge. They waited for low water conditions to try it and descended by back paddling, which Wolf had found to be the best way to control a sluggish foldboat through a technical rapid like Boulder Drop. Helmets weren’t used in those days. Life jackets were old World War II surplus aviator vests. The combination of water tightness and dependable instant release for spray decks was not really available until Wolf designed it into later fiberglass models. Wolf mapped the river systems in Washington and applied the now-standard kayak rating system (Class I through V) to each section that he and his friends had run. His rating system was patterned after an earlier German system and adapted for the Northwest. Wolf later corresponded with clubs in the eastern U.S. and they adopted his system. Although he did not shy away from whitewater on his private trips, he was determined that foldboating should not become synonymous with whitewater. He called the sport “river touring” and developed a safety code for foldboat trips, just as The Mountaineers had done for climbing. For those interested in rapids, he stressed the enjoyment of “play spots,” places where a foldboater could surf and plane on jets, eddies and rollers. Wolf applied ideas from skiing, teaching maneuvers such as the “eddy-christy,” performed with a paddle-brace to bank the boat into the current. To show the sport in a favorable light, Wolf took along famous outdoor photographers like Josef Scaylea and Bob and Ira Spring to shoot newspaper and magazine stories of river touring and saltwater paddling and camping. Wolf and friends led the parade through Seattle’s Montlake Cut on the Opening Day of boating season and staged club races on Lake Washington. His overriding concern was that paddling should be presented as a safe and sane activity “so any kid could take up the sport.” He was proud that the early years of the Washington Kayak Club had no fatalities. Initially, Wolf and his friends did most of their boating on rivers. During the 1950s, they took vacation trips throughout the Northwest to waterways and communities that had never seen a kayak before, including the Fraser, Thompson, Parsnip, Peace, and Kootenai Rivers in British Columbia, the North Saskatchewan and Bow in Alberta, and the Snake and Clearwater in Idaho. They eventually moved to open water, exploring shorelines and experimenting with surfing along the Washington coast. They explored Puget Sound, the San Juan Islands, the Gulf Islands, the west and east coasts of Vancouver Island, and Barkley Sound in the 1950s and 1960s. Today, Wolf is discouraged by the way river kayaking has evolved. “If it isn't whitewater, it isn’t kayaking,” he laments. Despite his best efforts, the sport has become equated with high-risk whitewater and has a high fatality rate. Sea kayaking has retained a safe and sane image, but river kayaking has gained a reputation as an extreme sport. As a result, many in the public are reluctant to take up the sport. Conservation Through kayaking, Wolf became intimately familiar with the rivers of western Washington. Most of these rivers flow on beds of glacial sand and gravel, and very few have cut into solid bedrock to isolate themselves within gorges and canyons. One exception was the Cowlitz River, which carved the Mayfield and Dunn canyons in southwest Washington. In 1958, Wolf and friends boated these canyons for a Seattle Times picture story by Bob and Ira Spring. The canyons were at the center of a controversy, as commercial and recreational fishing interests tried to block construction of the Mayfield and Mossyrock hydroelectric dams. The Washington Kayak Club added its small voice to the debate, but to no avail. The dams were built, flooding these unique canyons. Having been too late to save the Cowlitz canyons, Wolf turned his attention in the mid-1960s to the Green River Gorge. After exploring and kayaking the gorge with friends, he returned with his wife to photograph it. He created a slideshow and approached the Washington State Parks Department to interest them in preserving the area. In a 1966 Seattle Times article, he described the gorge—just thirty miles from a million people—as “a ribbon of wilderness in our midst.” Thanks to public pressure, money was appropriated to purchase private land in the gorge from individuals, railroads and timber companies, thus protecting it from development. Wolf considers the Green River Gorge his legacy to kayaking in the Northwest.

The satisfaction and challenge of this work inspired Wolf to launch a new career in the early 1970s as the Northwest’s leading shore resource consultant. He realized that the lessons he learned from kayaking could be applied to fisheries, stream management and flood control. He was also a founding member of the Washington Environmental Council. He reflects, “I’ve had the privilege to do something not just for a client but for the public. Wherever you turn now in this field you make history.” Wolf adds that it is not his intention to become known for doing these things. He would rather stay behind the scenes and “let other people take hold of it.” As the afternoon shadows lengthen on Vashon Island, Wolf Bauer gazes across Puget Sound, which he has kayaked for over fifty years, to Mount Rainier, where he has skied, climbed and helped save lives even longer. He notes with satisfaction that Ptarmigan Ridge is visible on this fine day and admits that he’s “chomping at the bit” to go skiing at Paradise while the weather holds. In a quiet moment, he reflects upon his legacy. “I think my most lasting contribution will be my work in ecology, since I switched from engineering to environmental education.” This work has spanned over thirty years, and it has affected the entire region, from Oregon through Washington to British Columbia. For the mountaineering community, Wolf’s pioneering efforts in skiing, climbing, mountain rescue, and kayaking have set the standard for decades. Yet his most important contribution as a mountaineer is not his record of first ascents and descents, impressive as they are. It is the example he has set—a sportsman, at the top of his game, who devoted himself to making his sports safer and more accessible for all. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Continued <<Previous | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Next>> |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ©2005 Northwest Mountaineering Journal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Site design by Steve Firebaugh |