| Mission | Submission Guidelines | Editorial Team |

| Issue 4 | Archive |

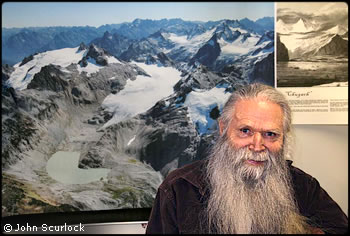

| Austin Post | ||

| by John Scurlock |

|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

During his aerial survey work in the 1960s, Austin placed his trust in the hands of military aircraft pilots on loan from distant tactical surveillance units. One such group of fliers came to Alaska from Guam. “We had no idea how long we’d have these fellows. Of course, when they arrived, we found them in the bar. I had hoped to photograph three or maybe four glaciers near the Juneau Icefield, but when I laid out the maps, they complained, ‘That’ll NEVER keep us here ‘til hunting season. Are you SURE you don’t have anything else?’ So we went back and drew up a huge list – and those boys helped us get hundreds of photographs we would have never had otherwise!” Numerous civilian pilots worked with Austin as well; the list reads like a Who’s Who of great bush pilots – Jack Wilson, Dick Ferrell, Celia Hunter, Bud Kimball, Ruby Sheldon, and Don Sheldon. Glaciers, gravel bars, isolated lakes – all were within the range of these men and women and their bush planes. Much of the work was with legendary Port Angeles airman Bill Fairchild, a favorite pilot with a Beech 18 twin-engine airplane that Austin was able to modify to accommodate five large survey cameras – one on each side, one in the nose, and two vertical cameras in the belly. The huge K17 cameras had such wide fields of view that only slight adjustments of the airplane by Fairchild (guided by Austin’s hand signals) were necessary for accurate aiming. “The cameras weighed 63 pounds each; they had six-inch objective lenses, and took 9x9 inch negatives; it was quite difficult to hand-hold them for long.” Imagination and inventiveness were traits that served him well throughout his career and made work tolerable in extremely remote locales where technical help from the outside was days or weeks away. “We shot mostly from about 10,000 feet, but sometimes we went as high as nineteen or 20,000 feet.” Oxygen wasn’t much of a consideration. “We were always on a tight budget and couldn’t afford that fancy stuff. It didn’t bother me much until we got above 18,000 feet or so. Extremely cold, of course. And once in a while, up real high like that, I’d have to give Bill a good shake when we noticed the airplane drifting off course. ‘WAKE UP, BILL!’ and he’d rouse around. The great thing about Bill was, he’d always give it a try. Sure, the weather would be awful, the other crews on the ground. But he’d say, ‘Let’s just go take a look,’ and up we’d go. We made a few flights where the weather followed just behind us, all the way to Alaska and back.” Just exactly how, over the years, did Austin keep track of more than 100,000 photographs? “The USGS staff kept bugging me to keep everything written down. So finally they got me a notebook, and I was supposed to keep all these notes. In those days we flew with the door off, as we hand-held those bulky cameras. During the first flight I tried it, the airplane hit an air pocket, and swoosh, out the door went the notebook. That thing is at the bottom of Glacier Bay, I suppose.” We laugh hard at that. Austin’s accomplishments don’t seem to spring from a great love and respect for bureaucracy. With thousands of hours flying over the most forbidding terrain in North America, were there any close calls? A few – some potentially serious, such as flying between the masts of a ship while running for home under low ceilings and poor visibility. Another time, catching a glimpse of land through fog that made them realize they were flying due west, out to sea, with not nearly enough fuel to make it to Japan. One flight in particular was unforgettable. “We were photographing the glaciers of Wyoming’s Wind River Range. The turbulence was terrible, with awful downdrafts, and the pilot, Dick Ferrell, had to run the engines at full throttle. Eventually the strain took its toll, and one of the supercharger gears locked up. The prop stopped turning in about one revolution. Dick feathered it and I asked him if we could continue? ‘No way’ was the answer, ‘the highest this thing will go on one engine is 5,000 feet.’ That was a slight problem since the ground in that area was over 7,000 feet high!” They turned toward flatter territory, looking for a ranch. By luck, a highway appeared, under construction but available nonetheless, and Ferrell made a smooth landing in front of an astonished grader operator. The road crew extended their hospitality, even loaning a truck, and Austin finished the trip with some ground-based visits to local glacial moraines. Eventually, his wife arrived from Tacoma for the ride home, which took a circuitous route through Yellowstone and up to the Canadian Rockies. “So it turned into a forced landing ‘Deluxe’,” he laughs.

Following our initial meeting in 2003, Austin and I schedule an aerial survey of Mount Bigelow on a bright summer day. We depart from Vashon and do some low-altitude maneuvering to escape Seattle’s busy airspace. After a rapid climb we head northeast over the mountains. “Maybe we should circle Glacier Peak a time or two,” I tell him. “Sure, why not?” We pass Bonanza Peak and bank for a closer look. The great north face rises up below us, the Company Glacier sweeping high to the dark cliffs of the upper headwall. “Really something, isn’t it?” I say and the reply is quick, “Sure it is, but let’s head for the GOOD stuff!” and he points ahead to Bigelow. I smile – this is hardly the first time Austin has seen Bonanza. A summer breeze makes the ride rough, but we circle many times past Bigelow’s north face. Austin shoots photographs each pass, one hand on the camera, the other held at an angle telling me how sharply to bank the airplane. He first photographed Bigelow in 1967, during his monumental project to catalogue all of the North Cascade glaciers, and now he is back. The twin-lobed rock glacier looks active from the air and might hide an ice core, protected from melting by a stony exterior and the shade of cliffs. “I helped build that trail…” he points down at the Hoodoo pass trail, on Bigelow’s west slope. “Let’s head over to Winthrop and take a break,” I say, and we turn north to the smoke jumper base there. In a few minutes we are on the ground by their jump plane. I flip up the canopy. The firefighters stare as I help Austin out of the cockpit – just who the hell are these guys, I can see them thinking. We stretch our legs, and after a short visit we are off again, circling leisurely over the Methow Valley’s ancient moraines and glacier carved valleys. Climbing high above the Cascades, we swing to the southwest. Even from there, we can see the Olympic Mountains far in the distance. Finally we run down green forested valleys to salt water, rolling onto the turf of Vashon’s airstrip. Roberta is waiting by the car. “I hope you boys had a good time,” she says. The gleam in Austin’s eye is his answer. In 2005, John Roper tells me that Austin wants to follow up our Mount Bigelow flight with an expedition on foot. Soon we have a small band of climbers, hikers, and geologists assembled. Few of us are actual scientists, but we share the pull of wild places and the desire to help Austin see if Eacas Glacier actually exists. The group consists of Roper, climbers Jim Nelson and Silas Wild, geologist Bob Krimmel and his friend Shelley Douglas, Austin’s son Dick and nephew Stuart Hubbard, wilderness traveler Jerry Huddle, skier and fellow medic Jim Lane, and me. We rendezvous at the East Fork Buttermilk trail, west of Twisp, where we will follow Austin back to ground he first covered as a youthful Forest Service trail builder. We argue over the privilege of carrying a folding lawn chair on our packs – at age 83, Austin is entitled to have the most comfortable seat in camp. A jovial hike through six forested miles brings us to a horse camp, the only mishap being a broken wine bottle and the tragic spill of its contents onto the trail. Fortunately, we veteran backcountry travelers have laid in extra stores for just such an emergency. The next day we amble up switchbacks, crossing open larch forest to the huge jumble of rocks below Bigelow’s north face. At first, isolated trees grow directly from the lichen-covered boulders, but as we climb we eventually come to a steep and unstable slope of scree. It seems obvious that things are active here, and we scramble upwards. From the top, we can see what looks like ice extending toward cliffs of the upper north face. “Can one of you youngsters get up there?” asks Austin. So Jim Lane, with his seemingly unlimited energy, heads upward. An hour later he tracks me down as I hike towards Bigelow’s summit. “Yep,” he says, “solid ice. With an actual crevasse, too.” Not only that, he has scrambled down ten feet to the bottom of the crack, which narrows to deeper ice. For Austin, the news is wonderful. “We can call it Eacas GLACIER for sure!” No glaciers farther east, I wonder? “Maybe Remmel, in the Pasayten,” he says. But that is so remote it will require pack horses. Besides, the aerial indications are not so promising as Mount Bigelow. Remmel will wait for some future band of rag-tag glaciologists, and after the long day in warm fall sunshine, we gather and roll down the trail to camp. A snapping fire and tequila shots that evening fuel our imagination for future adventures. For the love of iceIn September 2006, Austin is again looking for ice in the eastern North Cascades. After a search in the valley below Liberty Bell’s east face, we are back down at the cars, Austin relaxing in his lawn chair throne. “I’d like to show you fellows some things in Washington Pass Meadow,” he says, so we make the short drive to Washington Pass. Bathed in the warm sun and light breezes of an early fall North Cascades afternoon, we rustle through a few trees out to the meadow. We spread out, and soon Austin and I are off to the north, where an old abandoned trail appears. “I led a trail crew through here in 1947,” he says. “Let’s head this way.” So the two of us set out, the faded path easy to follow in the open meadow. “I’d like to see if we can find any Glacier Peak volcanic ash up here,” Austin says, and I wonder how we’ll do that, with only a jackknife for digging. But after we walk for half a mile, we find an eroded bank beside the trail. “What the hell, I can always sharpen this thing later,” I say to him, so we sit and dig for 20 minutes, using our hands to smooth the sides of our tiny pit, looking for layers – geology in perhaps its simplest form. We are lying on our stomachs, peering into a hole in Washington Pass Meadow, dust on our hands and clothes. “I don’t see anything that looks good,” he says, “safe to say, no ash here!” We wander back to the east, off the trail now, out in the open meadow, and I can hear the voices of our friends in the distance. “I think I’d like to take a break,” Austin says, and before I can answer, he sits down in the grass and lies over on his side. A moment later, he’s asleep. I might as well enjoy the moment, so I sit too, Liberty Bell’s amazing monolith rising up ahead of us; this is not the first time Austin has napped in this meadow, I am sure. The sun drops a bit to the west, and I am thinking that the old trail boss is home, for sure. Austin Post turned 85 on March 16. We are already making plans for the next trip to search for hidden ice in the North Cascades. |

|

||||||||||||||||

<<Prev | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|||||||||||||||||

| ©2007 Northwest Mountaineering Journal | |||||||||||||||||

| Site design by Steve Firebaugh |