|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

n the summer of 1968, Steve, Leon and I were looking for enlightenment, and girls, whatever came first. We sat cross-legged in Steve’s basement bedroom listening to Lou Reed of the Velvet Underground whine and scream his way through “Heroin.” We held the Andy Warhol cover and slowly peeled back the banana peel to find underneath, a banana. We trooped down to the Ave, near the University of Washington, pooled our coins to cover the five dollars we needed for a plastic sack of grass. Weeks later we found out it was real grass; that explained the manure smell. We sat through too many showings of 2001, A Space Odyssey, blasted against our seats as astronaut Keir Dullea rocketed through a celestial light show to the far corners of consciousness and beyond. We read Kesey, Hesse, Camus, and Kerouac but for Steve and Leon Kahlil Gibran’s The Prophet was the Holy Grail. It was heavy they said and I was so ready for heavy. Gibran’s face, gauzy and guru-like stared at me from the cover, but what I found inside was anything but heavy.

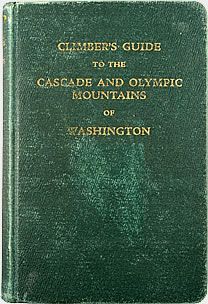

My soul and I were soon on the path to throwing Gibran’s gooey confection through a window. I would have to look elsewhere for enlightenment, outward rather than inward—to the mountains. In 1968, mountains without trails to the top seemed impossible. That spring I climbed Mount St. Helens with the Snohomish High School Mountaineering Club. Above the Dogs Head, our rope team wandered onto the Forsyth Glacier where we encountered actual crevasses, dark and bottomless. Okay, they had bottoms and I could see them, but that did nothing to ease my anxiety. We were rescued by the sudden appearance of Ome Daiber (he seemed to show up everywhere), who good naturedly led us through the web of crevasses to the summit. Mountains were scary. That summer Mark Jarrett lent my father his copy of The Climbers Guide to the Cascade and Olympic Mountains of Washington. I picked it up almost by accident and found myself immersed in a world of buttresses, bergrshrunds, arêtes, spurs, chutes and couloirs, where people fought through heavy brush and timbered blowdowns, up gullies of talus, snow and ice to notches, cols and saddles to climb fingers, cracks, faces and pitches of class three, class four, class five, even class six, using safety pitons, stirrups and shoulder stands on rock that was crumbly, broken, rotten, loose, polished, solid and shattered. And always the routes, with purity of aspect, traversed obliquely. Heavy. Two years later at the University of Washington I found girls, finally, and they climbed. Fear gave way (well, almost) to exhilaration as, first in well-worn Munari boots and later in chunky blue Robbins boots, I stepped where there was nothing on which to step, crimped my fingers on slivers of rock, and climbed upwards. Sometimes I would jam my hands and feet into cracks to climb. My mantra was “Jam Goddammit!” Under the tutelage of Al Givler, Mark Weigelt, and Julie Brugger, I began to lead around blind corners, up open-book cracks, lay-back off wafer-thin flakes, stem off-width chimneys and smear on smooth slabs. With my rock hammer, I bashed wide angle pitons in cracks and tapped RURPs into thin seams. Hanging from my ponderous rack were bongs, Leepers, knifeblades, Lost Arrows and more. My pack was loaded down with slings, biners, rack, rope, hammer, and that little burgundy book, which had a big chunk of my life in it. I just needed to find the right routes. (Mark Jarrett would never see that book again.) I spent hours in almost semiotic delirium reading and rereading route descriptions looking for grand truths, and, frankly, easy routes of cool mountains. I would trace my fingers along the dashed routes on Dee Molenaar’s hash-marked sketches, imagining every move (too many of them nailed only in my imagination), searching for answers. When Beckey said tricky to describe the 12-foot 5.7 slab pitch on the west ridge of Prusik, did he mean scary tricky or parlor magic show tricky? What did an objective buttress toe look like, and was there such a thing as a subjective buttress toe? And while a mountain feature could be a toe, a foot, a finger and an arm, a rib, a midsection, a nose, why no leg? How pleasant was a pleasant rock section? How hard was hard? How exposed was exposed? I would never find the answers unless I ventured into the field to gather empirical evidence. Mount Index—Normally

Who was companion, did Cliff and I need him, and would I get to be L. Chute or settle for G. Tepley? We had tried the North Peak a year earlier, our attempt ending at Lake Serene in the inky dark pre-dawn hours of a stabbing cold October morning. We decided to sleep on the frosty ground until we could see something. Twenty minutes later, shivering uncontrollably, we retreated, falling down, and sometimes off, the trail to the car and on to a huge pancake breakfast at Sheltons in Leavenworth. When the sun came out we nearly ripped our britches au chevalling up Chumstick Snag. A year later we found a companion, Tom, a consumptive looking lad, straight out of Great Expectations, who was hitchhiking across the country from New England to climb in the Northwest. Cliff picked him up and he stayed all summer. Hoping to put the previous year's humiliation behind us, we headed for the North Peak in the afternoon and bivouacked at the base of the climb, a waterless camp. That night, as I slept, Cliff and Tom drank all but two of the five quarts of water we had brought with us. Beckey’s route description gave us some hope that we would find water above:

We were left to intuit the words normally. The year had seemed normal: more underachievement at the University of Washington, graduating with no fanfare, no job, no money and no girlfriend. Yep, the year was normal all right. But was my normal Beckey’s normal? We would soon find out. We kept just right of the crest, ascended left sharply and angled right, climbed an exposed pitch, climbed ca. (caw?) 30 ft. up a rock basin. We traversed, turned up, traversed again and continued up to...no snow. I now knew normal and I knew we would be thirsty. At the summit we drank our last water and watched the happy people in their inflatable rafts on Lake Serene. I sucked on grape Kool-Aid crystals for the next seven hours as we rappelled down steep brushy gullies, loose rock outcrops, nearly vertical pitches and oblique slabs and finally to Lake Serene where we could normally expect to find water. In the dark we stripped off our clothes and jumped into the icy waters of Serene. Refreshed and relieved to be alive, I was left to ponder the word normal: naturally occurring (I was sort of natural); free of mental disorder (I was fairly well-ordered); perpendicular to a tangent at a point of tangency (beats me). Normal, normally...And then I recalled that in 1962 Thomas Kuhn had written The Structure of Scientific Revolutions in which he stated that scientists work in a system that he called “normal science.” In normal science, the theories are accepted without question. The theoretical system is a “paradigm” which everyone assumes is true. Oh yeah, I was a sucker for a new paradigm. God, Beckey was deep. Whatever he said was good enough for me. Perhaps snow that wasn’t snow was the new paradigm. Perhaps if I had actually climbed it in mid-season instead of mid-September...

Cathedral Peak—Requiring Hands

After two days of hiking, Jim, my father and I stood 30 feet from the summit cross and looked at our hands. We each had a set, but they seemed inadequate as we looked into the depths of the cleft that separated us from the summit. We needed to get our hands on a rope. I imagined myself taking a long step to the foothold mere feet away. Then I imagined myself grasping the rock with my hands, as Beckey wished, and striding proudly to the summit cross. I opened my eyes, looked into the abyss, imagined myself missing and pinballing to a messy death. I stepped back, uttered an inappropriate oath so close to Cathedral’s summit cross and announced, “I’m going to get the rope, dammit.” I ran, jumped and slid down the scree slope to Cathedral Pass, grabbed the rope, and jogged-walked back to my two partners who were stretched out on the flat rock half-asleep in the afternoon sun. I unwound the rope with my hands, tied the bowline on a coil with my hands, and then, safely belayed, stepped across the chasm where dream and reality merged as I grabbed the rock with my hands, and, shortly thereafter, stood on the summit. What had Beckey meant by requiring hands? Would there be times in the mountains when I would be asked to climb with my hands tied behind my back? Was he talking about Adam Smith’s invisible hand, the lynchpin of his free-market economic theory or was he alluding to the famous Japanese koan about one hand clapping? Was hands a metaphor for cajones, and did I lack them? Scratch the surface and you began to peel away layers of meaning. And I feared I would never get it. Luckily in the next editions requiring hands had been replaced by “cross a gap (awkward mantle)...” Ah yes, awkward I knew.

Perry Creek Route—Open Forest

Five level miles up the Little Beaver Trail and then a relaxing five miles through open forest and huckleberry undergrowth and we would be comfortably camped in splendid isolation at the base of Twin Spires. The other approaches into the Redoubt-Spickard area (a part of the Skagit Suite—not to be confused with Suite Judy Blue Eyes—a Cretaceous-age metamorphic complex composed of Skagit Gneiss, no schist.) seemed so, so, well, long and sweaty, while a walk through open forest and huckleberry undergrowth seemed to be the height of sylvan genteelness. Our dreams of a spot of tea in the shadow of Twin Spires vanished after a short while when the open forest closed in around us. We humped our packs up and over blown down cedar, Doug fir and hemlock. Yes, we encountered the huckleberry undergrowth, but it seemed a much larger, somewhat alien species—Seymour in Little Shop of Horrors. Devil’s club and ragged gangs of dwarf fir grabbed and pushed at us all afternoon. Through the hellish snarl of forest we slogged, set upon by some of the biggest mosquitoes I had ever seen. The buzzing was that of the distant drone of huge airplanes. Sweaty and swatting we searched for the head of the valley that would deliver us from this nightmare of open forest and huckleberry undergrowth. At one point Jim stepped up onto a pile of fallen trees, caught his foot between two, twisted left and pitched backwards, held down by the weight of his pack. With lot of help, he was able to right himself and limp onward. As the sun set behind Twin Spires, we found our first clearing, large enough for our tent, and there we stopped. The mosquitoes partied all night outside the tent daring us to come out and relieve our bladders. In the morning, the bugs had been chased away by the rain. Ahead of us was an impenetrable stand of slide alder. We longed for the open forest and huckleberry undergrowth.

Eventually Jim, Dad and I climbed Spickard and later Redoubt, but we opted to return via Whatcom Pass and the Little Beaver trail. Jim would suffer severe back pain for several years before finally having an operation and my father would nurse a sore knee for the better part of a year. Had I missed some nuance in Beckey’s description of Perry Creek? Once again I had to look beneath the surface. Much later I came across an article by the novelist John Berger, who had written that a forest is not the trees, the dense undergrowth, or the mosquitoes, but what exists between. And it came to me, a metaphoric slap to the face: Beckey was gently reminding me to look beyond the trees to see the forest. He was inviting me, as Aldous Huxley had done in 1954 with his ground-breaking book, to walk through the doors of perception. I wasn’t sure if Beckey wanted me whacked out on mescaline when I did. Many have been the times since our trip that I have yearned to return to the open forest of Perry Creek and knock on that door and say, “Forest, let me in. It’s Mac.” I fear, though, that I am doomed to see only the trees, the huckleberry, the devil’s club and the mosquitoes. Beckey's ground-breaking quidebook, first published in 1949 by the American Alpine Club, will be sixty next year. It was followed 12 years later by the little red book that transformed my life. Over the years it has been expanded into brown, red and green editions, followed by pastel and enviro-friendly hued editions. Perhaps we will see tie-dyed editions in the near future. In homes all over the Northwest and beyond, climbers spend far too much time interpreting the word according to Beckey. And sometimes the word was good. It is no wonder that the Climber’s Guide to the Cascade and Olympic Mountains and later the Cascade Alpine Guide have been dubbed “Beckey’s Bible.”

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ©2008 Northwest Mountaineering Journal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Site design by Steve Firebaugh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||