|

|

||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

he news clippings have yellowed and the black and white photos have tinted with age. Yet the pages of my grandfather’s scrapbook still evoke feelings of adventure and awe. In 1968, the year my grandfather Harry passed away, I was 18 years old and a backpacker but not yet a climber. A year later, a few buddies and I began our climbing careers with ascents of several Northwest peaks, including Mount Rainier. After that initial foray into mountaineering, my father gave me a scrapbook that had belonged to his father, a record of Harry Venema’s 1908 ascent of Rainier. It was only then that I learned that my grandfather had ever climbed at all. He was 23 years old at the time and he made the trip with a group of twenty-five young men from the Seattle YMCA.

While my grandfather’s scrapbook has no written diary, it contains many black and white photographs and two newspaper articles written about the climb (see sidebar). A few facts help place a 1908 climb of Mount Rainier into perspective. While there is evidence of an undocumented 1855 summit climb by two surveyors, the first recorded ascent of Rainier was made in 1870. The first ascent of Rainier by a woman was in 1890. By 1900 just over 30 parties had reached the summit (roughly 160 climbers). While those numbers are small by today’s standards (roughly 10,000 climbers now attempt the summit annually), group ascents like my grandfather’s were not unheard-of near the turn of the century. In 1897, fifty-eight members of a Mazama party reached the summit crater, and in 1906 sixty-two members of a single Sierra Club group summitted. The Mountaineers also sponsored group climbs and another large YMCA party made the climb a year before my grandfather. It’s impossible to know the exact details surrounding my grandfather’s climb. Yet the photos, clippings, and historical record make informed speculation possible. Imagining and researching a climb 100 years ago evokes a feeling of uncertainty and discovery much like the excitement of planning a climb today. For my grandfather’s 1908 climb, published descriptions of the climbing route were probably hard to find. Fortunately, the climb leader had previously ascended the route. That all the men underwent physical exams and that a news article was published before the climb suggests that planning had been in progress for some time. Some men had been training for as long as three months. Since telephone service at that time was not universal, most communication among team members would probably have been via the YMCA bulletin board and U.S. mail. It's likely there were several group meetings for planning and instruction as well as group training hikes. By the time my grandfather and his partners met at the Seattle train station for their journey to Longmire, they had undoubtedly met several times and had spent considerable time together during the lengthy preparation period. My last ascent of Mount Rainier was in 2004 via Sunset Ridge, a route first climbed in 1938. The climb was planned entirely via email with partners Matt, Chad and Seth. While we had established a tentative timeframe for the climb a few weeks earlier, the final departure date was set only a day or two before we left and only after we carefully checked the Mount Rainier weather forecast on the web. I photocopied pages from one of the excellent guidebooks available and scoured the internet for published trip reports from others who had done the route. We would be heading up the mountain with a very detailed description of what to expect. We were far less knowledgeable about each other. I knew Matt through cragging at Smith Rocks but had never climbed with him in the alpine. I had met Chad via an internet climbing web site and had climbed with him once. Seth I had also met online but had yet to get out climbing together. Chad and Matt met for the first time in Portland at 3:00 a.m. before driving north to pick me up. By 3:45 a.m. the three of us were leaving my house and on our way to Paradise where we would all meet Seth for the first time.

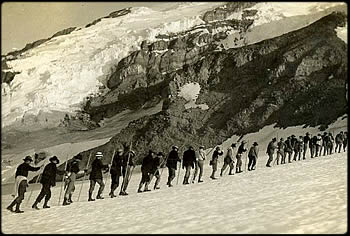

My grandfather’s trip from Seattle to Longmire would have required a long day with several stages. The first leg would have been a streetcar ride from one of the Seattle neighborhoods to the recently completed King Street station. From Seattle to Ashford the party traveled by train. Arriving at Ashford in early afternoon, they’d transfer their belongings to a horse-drawn carriage, then ride thirteen miles to Longmire, where they would spend the night. Then the real work began! While Paradise was already well established as the climbing hub of the park, the road from Longmire (2760ft) to Paradise (5400ft) was completed only as far as the Nisqually Glacier. The YMCA group likely spent the second day of their adventure hiking from Longmire up the old Paradise River trail to Camp of the Clouds, a climbers’ and hikers’ tent camp just above Paradise on the east shoulder of Alta Vista. There they would have been served a hot meal, probably among other alpine travelers, and provided a place to try to sleep before their summit attempt the next day. Matt, Chad and I arrived at Paradise at 7 a.m. after a fast and uneventful drive from the Portland area. We found the parking lot already fairly crowded with cars. We found Seth, introductions were made and we headed into the Ranger Station to register for our climb. Not having made an advance reservation, we had to juggle our itinerary a bit since the camping quota had already been filled for one of our planned alpine zones. We each paid $30 for our annual Rainier climbing permit, got an updated weather forecast from the ranger, and then sat down to breakfast at the historic Paradise Inn (built in 1916, eight years after my grandfather’s climb). After breakfast we all loaded into my car to drive back down to the West Side Road to the start of our approach hike, leaving Seth’s truck in the Paradise lot for our return in three days. Our first day’s hike was to a camp at 7600ft, and the next day we moved to a higher camp at about 11,000ft. We were well equipped and our camps were comfortable. Chad and Seth each had a Gore-Tex bivy sack and Matt and I shared a 3 ½ pound Gore-Tex tent. Our two MSR white gas stoves made quick work of melting snow for drinking water, and our freeze-dried dinners were ready almost immediately after adding hot water. Even though wind and blowing snow prevented us from getting much sleep the second night, our down bags, sleeping pads and waterproof/breathable shelters enabled us to stay warm enough to get some rest before heading for the top the next morning. While a few early south-side climbers made a high camp at the present location of Camp Muir, the first shelter hut there was not constructed until 1916 and one-day round-trip climbs from Paradise to the summit were quite normal (much more so than today). My grandfather’s photos provide no indication that his party camped anywhere above treeline. One photo (see top of page) was clearly taken on the Muir Snowfield. Most of the climbers appear to be dressed in tweed jackets or wool sweaters, almost certainly over wool shirts and long-johns. The sun is already well up when the men are midway up the Muir Snowfield. With no high camp planned, their start from their treeline camp near Paradise appears quite late. Both the desire to climb in the warmth of the sun and the difficulty of seeing one’s path in the dark must have argued strongly for the later start. While they probably wore nailed boots for traction in the snow and ice, their only other personal climbing equipment appears to be an alpenstock, a six-foot wooden staff often used by early climbers in lieu of an ice axe. They are never roped together while traveling on the glaciers and they seem completely unfazed standing at the edge of a deep crevasse for a photo opportunity. The scrapbook has no mention of the exact route they took to the summit, but one photo shows the men climbing what was apparently a fixed rope through a rocky section that is probably Gibraltar Ledge, the route of the first ascent and the most commonly climbed route at that time. The men probably stuffed a bit of food in their pockets, but most appear to lack even a canteen. Nowhere in my grandfather’s photos is any member of the party seen carrying a pack above treeline. (I wonder if they ever used the phrase “fast and light?”).

At 11,000 feet on Sunset Ridge, our team of four was packed and ready to move by 3:30 a.m. on our summit day. We strapped on harnesses, tied into a 60-meter perlon rope, attached our rescue prusiks in case of a crevasse fall, and slipped our steel crampons onto our plastic climbing boots. The air was cold enough that I started the day’s climb wearing a Polarguard parka over a wicking base layer and a light fleece insulating layer. Aside from wool socks, every article of clothing I wore was of synthetic fabric. With steep terrain and risk of falling rock or ice, we all wore helmets with lightweight headlamps to light our way in the dark. We each carried an ice axe to start, and each of us had packed a second ice tool which we used higher up where the slope steepened. Though we never used them, we carried aluminum pickets and ice screws in the event they were needed. We each carried a pack that weighed nearly 50 pounds. Due to the small number of Rainier climbers back in 1908, my grandfather and his partners probably saw few if any other climbers during the climb or on the summit. Judging by their late start, they probably didn’t reach the top until at least noon, and possibly much later. The photos show sunny and clear weather, with many in the party using the common sunscreen of the day, soot and grease! They must have been both dehydrated and hungry upon reaching the top, but they stayed long enough to take photos. An early Kodak folding camera, weighing at least two pounds, was likely used for all climbing and summit photos. When they started descending, many hours of travel remained before reaching camp. Two members barely made the top and they may have slowed the descent. They most likely descended their route of ascent and, as they had on the way up, passed by Camp Muir. A long and tiring slog down the Muir Snowfield (photos show they did their best to glissade when possible) brought them back to Camp of the Clouds, where they celebrated (and quite likely consumed a lot of food!) before sleeping. They surely would have had time for breakfast the next morning before hiking back down to Longmire to board the carriage followed by the train back to Seattle. As Matt, Chad, Seth and I traversed the summit of Liberty Cap and dropped into the saddle below Columbia Crest, the mildly threatening cloud cap dissipated leaving us under clear skies. During a brief stop to get fresh water from our packs, I applied my high-SPF sunscreen as I watched dozens of climbers topping out on the Emmons Glacier route and more above us on their way up to Columbia Crest. Upon reaching the top, we found many more climbers celebrating their accomplishment and, as we soon would be, taking photos with compact and lightweight digital cameras. A nearby climber was on a cell phone announcing his location to family back home. Several small parties could be seen approaching from the far crater rim. Most of those climbers would have ascended via Disappointment Cleaver or by one or two other south-side routes.

While the Gibraltar Ledge route that my grandfather climbed remains popular in winter and early spring, by June it is typically abandoned for safer and easier alternatives. Our team of four descended the Disappointment Cleaver route, following the deep trough that is created in places by the sheer number of climbers using this route. On the way down we passed several rope teams still on their way up. Among these were some commercially guided clients who had paid hundreds of dollars to be led up the mountain, their guides communicating with each other via two-way radio. We passed several tents at Ingraham Flats before rounding Cathedral Ridge and crossing the Cowlitz Glacier to Camp Muir. We passed a cluster of colorful tents pitched in the snow, crested the ridge and dropped our packs for a few minutes rest. Where my grandfather had likely encountered only an empty, windy, broad saddle, we encountered a crowded and busy hub of activity. From the first public cabin built in 1916, Camp Muir has become home to a small ranger’s A-frame, a guide hut, a cabin for guided clients, solar outhouses and on this sunny Sunday in June was crowded with people. A full-time Park Service ranger was present, along with commercial guide staff, climbers returning from the summit, climbers arriving to ascend the next day, and many day-hikers up from Paradise. The four of us soon continued our descent, hopped in Seth’s truck at Paradise for the shuttle back to my car, and before long were enjoying a post-climb meal and beer at a restaurant a few miles down the highway. Afterward we said our goodbyes, and Seth headed north to Bellingham as the three of us turned south toward Portland and home. While the YMCA group must have been eager to get home to a real bed and some real food, they must also have enjoyed the camaraderie of the rail trip home. All party members had summitted, and one can imagine the feeling of accomplishment that surrounded the group and the rehashing of climbing exploits that must have occurred during the long train ride. Upon their return to Seattle, a victory party was probably celebrated at the YMCA with family and friends. Perhaps that is where a newspaper reporter got the details he needed to write the article that would make their accomplishment known to all of Seattle. After a three hour drive down I-5, and no more than twelve hours after standing on the summit, I was home uploading onto my computer digital photos of our climb. I copied them onto three CDs and the next day mailed them to my three partners. That day I also typed up an account of our climb which I posted with a selection of photos to a local climbing web site. Although that trip report may not have been read by much more than a thousand readers, it was available to hundreds of millions of internet users all over the world the moment it was posted.

Sunset Ridge marked my 25th ascent of Rainier. While I have climbed several routes that were more difficult both technically and physically, it was a very rewarding climb, definitely more challenging than the commonly done routes, and I felt proud to have climbed it. But looking at my grandfather’s photos and reading the newspaper articles, I’m compelled to compare our climb with what he did so many years before. Even when I started climbing in 1969, the equipment, clothing, techniques and planning aids we had at our disposal were far beyond what my grandfather and his partners had available in 1908. By 2004 those differences had become even more dramatic. With the long journey to reach the mountain, the approach hike, rudimentary clothing and equipment, and climbing to the summit without a high camp, one can’t fail to be humbled by what the YMCA group accomplished so long ago with so much less than we now take for granted. If I could talk to him today, I would love to tell my grandfather how much more impressive his climb was in 1908 than mine in 2004. As far as I know, Rainier was the only serious climb he ever made. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ©2008 Northwest Mountaineering Journal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Site design by Steve Firebaugh | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||