|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

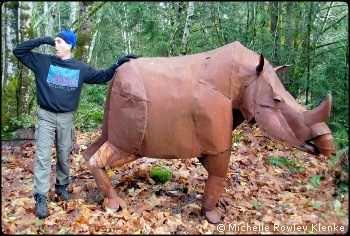

But this story isn’t just about me. It’s about me and about half-a-dozen others who are patients in the asylum of dumpster diving lunatics. Let me preface with the following advisory: dumpster diving is not for you. Please don’t assume that I’m writing this to win you over to our cause, to shanghai you into our asylum. This article is to help you make an informed decision when you get invited to “go climbing” with one of us. You can evaluate the destination for what it is and be prepared with your excuse, something like “Sorry, I won’t be able to make it. I’ve got to get my nose hairs trimmed that day.” Opening the Lid You may be wondering what exactly dumpster diving is. In fact, at a recent gathering, a friend’s new girlfriend thought we were talking about the real thing and she told us about a support group dedicated to this activity. I took it upon myself to educate her—between her eye roll and her yawn—on the place that dumpster diving occupies in the world of peakbagging. The pinnacle (so to speak) of dumpster diving is to summit a little, forested peak in the dead of winter, usually in pouring rain, by traveling through sopping brush, across sodden ground, and over dripping fences (or sometimes under them), with your climbing partner nagging you from behind about your idiocy, reminding you over and over that you’re on private property, that the car you left at the gate will be towed if you don’t hurry, and that his nose hairs are tickling and causing him to laugh. No, he is not laughing at you and what you are doing. No, not at all… Peering over the Rim For those of you who are still reading and would like to learn the background, I shall define dumpster diving more thoroughly, or at least dig into the dung heap from whence this toadstool of an activity sprouted. In December 1998, Jeff Howbert and John Roper were out in the woods bagging tasteless little ’stools near Mount Erie on Fidalgo Island. They had set their sights on Sares Head, two miles northwest of Deception Pass. Howbert recalls: “On our approach to Sares Head we parked on some mucky spur road. At the place where we got out there was a pile of garbage, probably left by someone saving a few bucks on dumping fees. Amongst the garbage was an old leather car seat. I plopped into the sagging seat and declared that this spot would serve as the Sares Head basecamp. The expression ’dumpster diving’ popped into my head at that moment. The phrase was a spontaneous inspiration. There was no conscious process, no design contest, no panel of judges.”

A Dumpster’s Contents Revealed If you ask what defines a mountain, you’re likely to get several different answers. Some people will answer based on aesthetics (“it must have exposed rock walls, etc.”). Others will provide an elevation cut-off (“a mountain must rise at least 3000ft above sea level”). But how would you classify a completely forested peak—like a peak in the Great Smoky Mountains—that is two times higher than a smaller mountain of no consequence with rock outcrops all over it? Or how can a low Himalayan peak of 8,000ft elevation even be considered a mountain as it cowers beneath the juggernauts above it? Clearly, the definition of a mountain is subjective. In the 1970s the idea of prominence germinated and grew into something worthwhile as a way to compare mountains with each other, especially mountains close to each other. The creation of the prominence measure doesn’t excuse dumpster diving as an activity but it does help to explain it. Prominence is a completely objective, mathematical feature of any raised terrain, be it a mountain or even a lowly golf course knoll. Simply stated, a mountain’s prominence is the measure of its rise from the lowest saddle (called the key saddle or Noah’s saddle) connecting it to higher ground, usually another summit (called the mountain that “holds” the subject mountain’s prominence). The direction of measurement always follows a divide, even if an imperceptible divide across a flat expanse, and therefore never crosses a drainage, such as a creek or river.

The prominence of many mountains can be determined quite easily because the higher peak is nearby and the saddle between them is easy to find. For example 9,131-ft Mount Shuksan is connected to 10,781-ft Mount Baker through a 4720-ft saddle, Austin Pass, near the Mount Baker ski area. This saddle gives Shuksan a “clean” prominence of 9,131ft - 4,720ft = 4,411ft. On the other hand, the key saddles of some peaks are not so easy to find and take a fair amount of map reading to suss out. Take for instance 14,410-ft Mount Rainier. If you follow a divide the entire way, the next-higher peak is actually 14,421-ft Mount Massive in central Colorado. The divide between them is literally thousands of miles long even if the direct crow-flying distance between them is somewhat less than a thousand miles. The key saddle is Armstrong Pass (also known as Okanagan-Shuswap Pass) in the Canadian Rockies, 100 miles north of the International Border. The elevation of Armstrong Pass is only 1,200ft, thus giving Mount Rainier a staggering 13,210ft of prominence. In fact, Mount Rainier is ranked 21st on the world prominence list right above K2 (P=13,189ft) and right below Kinabalu (P=13,455ft), the highest point on the island of Borneo. What does all this have to do with dumpster diving little summits in the Northwest? So we know that every point of land can have a prominence value assigned to it. If you designate a certain prominence value as a threshold between that which is worthy to be called a “peak” and that which is not, you can set about finding all such peaks on the topographic maps within a certain region. This is what Jeff Howbert, curator of the peakbagger’s asylum, did about ten years ago for Washington State. On his website he lists all the points (“peaks”) with P≥400ft, whether they have an official name or not, as well as lesser summits with P<400ft but nonetheless named on the map. This he calls the Master List. Howbert’s data soon infected a few of us peakbaggers and we

consequently admitted ourselves to his asylum. Basically, we decided

that we would willingly climb any of these peaks, no matter how small or

inconsequential, even if it meant ridicule from supposedly

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Continued 1 | 2 | Next>> |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ©2009 Northwest Mountaineering Journal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Site design by Lowell Skoog | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||