|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

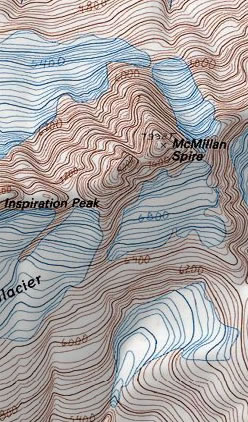

Another seventeen years passed before I crossed paths with McMillan, while traversing below it with Chuck Sink, enroute to Terror’s North Face. The smooth gneissic slabs were strewn with loose rock and tottering blocks of ice below the big spires. One really couldn’t hang around and admire the view; something was constantly falling or moving. Sheets of glacial melt water flowed over the rock creating a ruddy brown slime underneath; possibly the slipperiest surface I’ve experienced next to verglas. The thing to do, we decided, was to keep moving, climb Terror, and get the hell outta there. Besides, even though the skies were cloudless, and the weather prediction fine, in the Pickets, snow and rain will materialize out of nothing and a “Jack the Ripper” London fog could blot out the terrain in minutes. Just look at a precipitation map of the North Cascades and you’ll know what I mean; a swath of green that indicates 150 inches of precipitation per year extends from Bear Mountain and Redoubt on down to the Pickets. Other places I have skied and climbed — Alaska in the spring, Patagonia in summer or Nepal in autumn — cannot compare with the Pickets any season. Snow changing to rain in winter while descending into Stetattle Creek, is without question the coldest I’ve ever been. There is something about ice water evaporating off warm skin that chills the toughest of climbers.

But once desire gets a grip on you, logic and sanity are easily waived. In 1986 Peter Keleman and Rachel Cox put up the North Buttress on East McMillan Spire over several days in August. Following the North Face by Bryce Simon and Doug McNair in 1976, it was the second route on the face. I wanted to repeat Rachel and Peter’s route, so in 1991 cajoled my friend Paul Sloan from Nashville, Tennessee into going. We got about nine pitches up and became thoroughly lost and confused as to which way Rachel and Peter had gone. The rock was wet, the pro was bad and my shoes were slipping. We rappelled off a slung horn and knifeblade; seventeen years later they were still there, faded and rusty. Four years later Joe DeMarsh and I hiked all the way in Sourdough Ridge in August to attempt the buttress, but weather and a ravaging black bear thwarted our try. In 1996, Dana Hagin and I put up a new route on the Northeast Buttress of Inspiration. We rappelled down from the West McMillan/Inspiration notch, changed into rock shoes, crammed everything into the follower’s pack, and began picking our way up the not-so-solid dark metamorphic rock. A high bivy on a perfect ledge, with a small snowbank, was our reward for a day of delicate climbing up large loose flakes and blocks. Pointing over to East McMillan, I said to Dana, “Now if you think this is fun, we need to climb that face over there. Yeah that one with hardly any cracks, and those green and brown patches everywhere.” The Piglets (as I affectionately refer to the Pickets) are not the high Sierra or the Sawtooths, but they are also not crowded. In the morning we finished up solid climbing on the airy buttress which finally merged with the upper East Ridge, the summit, and ubiquitous damp fog. During August of 2000, Carl Skoog and I carried climbing, camping and camera gear into Terror Basin for a five-day trip. In perfect weather we climbed the Pyramid, and a day later scrambled up the final class-four of East McMillan’s West Ridge. I had to get to the top of the thing by some route in order to become familiar with it. Carl and I peered down the vertical and shingled bad rock of the East Face like two small rodents sniffing for food. Not picking up any scent I remarked to him: “Someone will climb it eventually, but I doubt the needle on the fun meter will register at all.” On the other hand the upper North Buttress, although composed of schist, at least looked climbable. The sludge-colored rock had a paucity of cracks and horns, but at least was not sheer. Dana was keen to try the North Buttress in 2003, and with grueling packs laden with 10 days supplies, we traversed Sourdough Ridge to within a mile of the McMillans. Following Rachel and Peter’s program for the buttress in 1986, we climbed to a giant ledge four pitches above the toe, filled water bottles from a spring in a cave and bivvied. Unlike them however, we planned to rap the route instead of carry up and over. The easier strategy (in my opinion) is to get to the face via the col on Sourdough and return, rather than traversing around little Mac Spire and rapping down to the McMillan Creek Glaciers (like they did). Also I was keen to see if I could get the fun meter to at least register into the green by having an enjoyable summit day without any packs. We ascended most of their buttress, but still wavered westward for several pitches in confusion, and probably missed some solid and cleaner pitches in the process. Maybe we should just do a new route rather than “trying” to follow someone else’s line. High on day three, and going light, we found very enjoyable climbing up grey gneiss with small fissures and flakes placed at just the right spot for gear. After tagging the summit under blue skies, we rapped all the way back down to the giant ledge where we’d left half of our bivy gear. A year or two later Peter Hirst and Rolf Larson repeated the North Face/Buttress also and reported chossy, not very enjoyable climbing. “Perfect” was Dana’s comment. “Don’t want it to get too crowded in there.” But now my familiarity with the face was increasing, and I felt that steeper, harder and cleaner climbing could be found more over to the east of the North Buttress. The problem was who to partner with that would be willing to endure the long approach, the bad weather, and the huge uncertainty of reaching the top? Someone younger, stronger and full of enthusiasm!

Matt Alford, a Seattle P.E. teacher, was the obvious choice. We had ice climbed and done some biking together, and he liked remote alpine adventures. Still, some other qualities are needed by a mountaineer to pursue large unclimbed objectives: patience in stormbound tents, the ability to drink whiskey and play Scrabble, cooking skills, doesn’t snore, and above all can carry a heavier pack than me. Matt got high marks on all of these attributes, and so we set off for McMillan in August of 2005. The weather was unsettled, with a mix of storm days and good days. Would we have enough consecutive dry days to get up the route? Not heeding the previously mentioned North Cascades precipitation map, we plunged into the range laden with gear and food for ten days. We had just barely reached the campsite near the spire when the black, damp clouds set in, bringing rain and snow for five straight days. The finest of single-walled tents cannot endure a Pickets torrent of water, and by day three we were sponging the puddles frequently. Had we brought any, some toy boats would have provided additional amusement on the small bodies of water. With the food gone, and no improvement in sight, we exited out Sourdough Ridge and down to Diablo in one push. Matt’s knee suffered greatly from wearing crampons on the wet, steep heather below Elephant Butte. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Continued 1 | 2 | 3 | Next>> |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ©2009 Northwest Mountaineering Journal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Site design by Steve Firebaugh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||