|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

The automobile was just beginning to transform America. In the fall of 1908, Henry Ford started production of his Model T, known as “Tin Lizzie.” To launch the A-Y-P, the first transcontinental auto race across North America was started in New York City at the exact moment that President Taft opened the exposition in Seattle. Twenty-three days later, four cars rumbled into Seattle, with the climax of the race being the rugged crossing of Snoqualmie Pass. A wonderland of snow Professor Milnor Roberts of the University of Washington was one of the A-Y-P organizers. He proposed that the A-Y-P be held on the U.W. campus and he planned sports events for the exposition. At 32, he was young and energetic and, as Dean of the U.W.’s College of Mines, well traveled throughout the Northwest. During spring break from the U.W. in 1909, Roberts took leave from his college and A-Y-P organizing duties to enjoy an unusual holiday in the Cascades. On March 18, 1909, Roberts and a small group of friends arrived at the National Park Inn at Longmire on Mount Rainier for a week of skiing. The inn had opened just three years earlier. The recently completed Tacoma Eastern Railway terminated at Ashford, and from the train station to Longmire was a 13 mile journey by stage, sleigh or foot. The party included Milnor Roberts and his sister Milnora, their friend Carl F. Gould (a renowned architect who would later design the U.W. campus), Tacoma Mayor William W. Seymour and his wife, and several other friends. By special arrangement, the watchman of the inn allowed them entry, and they spent the next week enjoying skiing day-trips from the inn to the slopes of Eagle Peak, the Ramparts, and Paradise Valley. After skiing each day they’d return to the Longmire Inn for dinner and relaxation. Roberts later wrote: “One evening while we were celebrating with dancing and stunts, two of us elevated the mayor to our shoulders and paraded him around the lobby to the plaudits of the guests. As we passed the wide front door, it just happened to open, so we marched through it and out to the front steps where we dumped His Honor head first into a six foot snow bank.” The goal of the trip was to reach Paradise Valley on skis. The road to Paradise was still under construction and would not be plowed in winter for another 20 to 30 years. The Paradise Inn didn’t exist yet and the only structure in the area was a small ranger’s cabin. The shortest route from Longmire to Paradise was along the Paradise River trail, a six mile trek. Since the trail was unbroken through deep snow, the party made several trips toward Paradise, each time pushing the route farther up the valley. Two groups eventually reached Paradise. The first, including Milnor Roberts, reached the ranger’s cabin and enjoyed views of Mount Rainier rising above the head of the valley. Roberts wrote, “The only toilsome part of the journey was at Narada Falls, where we were forced to navigate our skis sidewise, in crab fashion, up the steep slope.” On March 24, two young ladies of the party, accompanied by James McCullough, watchman at the National Park Inn, skied to Sluiskin Falls, well beyond the point reached by the first party. Roberts wrote, “As both the ladies had ascended Rainier in summer, they could enjoy to the utmost the wonderful view of the snow-clad range spread out before them.” The Roberts party was enchanted by what they saw. In a letter to Eugene Faure written half a century later, Milnor Roberts recalled: “As we traversed the open slopes, now smooth with a great depth of snow, our skis hidden deep in the powder snow slid quietly along to make the only marks of man's presence even for a day, or at least the only visible one. The possibilities of Paradise as a winter resort so impressed us that I wrote an article for the National Geographic Magazine [and] published it with some of our photos in the June 1909 issue with the title ‘A Wonderland of Glaciers and Snow’.” Milnor Roberts and friends may not have been the first people to ski in Paradise Valley. Park rangers may have done it, or perhaps James McCullough, who accompanied the ladies to Sluiskin Falls on that bright spring day, had been there before. But the Roberts party came to Mount Rainier purely for recreation, and the story that Milnor Roberts wrote for National Geographic was the first on the subject to be published nationally. It’s fair to say that the March 1909 outing by Roberts marked the beginning of recreational skiing on Mount Rainier. His National Geographic article announced the birth of a new sport in the Cascades. Golden moment In the decade that followed the Roberts outing, a few hardy groups vacationed on Mount Rainier in winter. Among them were the Tacoma Mountaineers, who made their first winter trip to Longmire during Christmas week of 1912. Most of the Mountaineers were snowshoers, but at least one skier showed up for the trip. Joseph Hazard later wrote: “Miss Olive Rand struggled along on two lanky slabs of wood, with turned-up ends and a pair of simple loops for harness which quite failed to keep the runners straight or, for that matter, to keep them on her feet at all. She explained that the slabs were skis and that she had, in a misguided moment, borrowed them.” During the summer of 1916, construction began on the Paradise Inn, the first overnight accommodations to be built at Paradise. The following winter, the Mountaineers made special arrangements to stay there during their New Years outing. In July 1917, shortly after the inn opened to the public, the first ski tournament on Mount Rainier was held at Paradise. It was a ski jumping contest organized by the Northwestern Ski Club, co-founded by Thor Bisgaard, a Norwegian-born member of the Tacoma Mountaineers. The winner was Miss Olga Bolstad, just 20 years old, who defeated all the men to become the first ski champion of the Northwest. The Tacoma News Tribune declared: “Olga Bolstad, the pretty Seattle girl, was the greatest center of attraction among all the ski jumpers. Her lightness and grace made her a favorite with all, and she seemed to skim through the air like a bird.” Following her victory, Miss Bolstad was named an honorary, lifelong member of the club. Interest in winter recreation grew and the National Park Service (NPS) and Rainier National Park Company (RNPC) tried to accommodate it. In 1923-24, the Park Service began plowing the road to Longmire throughout the winter. In 1928, RNPC completed the Paradise Lodge and opened it to winter guests. (The Paradise Inn wasn’t open to the public in winter until the 1930s.) Due to demand that had been building for several years, Paradise Valley instantly became a public winter sports playground. In 1932-33, the Park Service cleared the road to Narada Falls throughout the winter and both the Seattle and Tacoma Chambers of Commerce held ski carnivals at Paradise. In 1934, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer sponsored the first Silver Skis race from Camp Muir to Paradise. The following year, the U.S. National Ski Championships and Olympic Team tryouts were held at Paradise. Big-time skiing had arrived on Mount Rainier. In the early years of the Depression, hundreds of cabins had been built at Paradise and Sunrise for use by summer tourists. Beginning in 1932-33, RNPC began leasing cabins at Paradise for rates ranging from $30 to $60 for the entire winter season. Starting with about a dozen cabins the first year, the number at Paradise grew to almost 100 by 1935. Rooms were also available for rent or lease in the Paradise Lodge (replaced in the 1960s by a flying-saucer-like Visitor Center), Paradise Inn, and several other buildings.

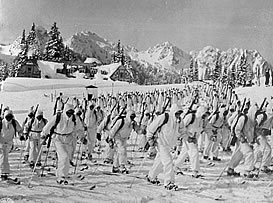

So began a “golden moment” of skiing at Paradise that lasted until World War II. With cabins buried deep in snow, ingenious skiers constructed a network of shafts and tunnels connecting the cabins to each other, the main lodge, and the surface. Veida Morrow wrote in 1934, “The underground city has become an established thing at Paradise. Frequently, even the chimneys were buried, and from a distance it was quite a sight during the dinner rush hour, to see tiny spirals of smoke emerging from innumerable mounds of snow, for all the world like a miniature ‘Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes.’” Concerns about fire safety prompted the Park Service to close most of the cabins after 1936, and skiers crowded into the other buildings in the valley. Every winter weekend there was night skiing under powerful flood lights, dancing on Saturday evenings, and ski trips and contests on Sundays. In 1937-38, Jim Parker and Chauncey Griggs founded Ski Lifts, Inc. to install rope tows at Paradise Valley, Snoqualmie Pass, and Mount Baker. Otto Lang, a Bosnian-born instructor from Hannes Schneider’s Arlberg school in Austria, ran a world-class ski school at Paradise that year. Ski fever was sweeping the Northwest. In a 1938 issue of Scholastic magazine, high school student Ralph Spencer wrote: “Skiing is like the measles. I was exposed about three years ago to the most glorious winter sport there is. The craze quickly spread among my friends, just as it is still spreading over the country…” War years In December 1941, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor swept the United States into World War II. Two months later, Mount Rainier became home to the 1st Battalion, 87th Infantry Mountain Regiment, which trained on the mountain in winter travel and survival techniques. The soldiers, many of whom were skiers before joining the army, celebrated their duty at Paradise by composing songs like the “Ballad of Sven,” with this chorus:

Paradise remained open to the public throughout that winter. The eighth annual Silver Skis race was held on April 12, and thirteen of the top twenty finishers in the race were members of the 87th Infantry. The following winter the mountain troops moved to Camp Hale, Colorado, where they eventually formed the famous 10th Mountain Division.

Wartime budget cuts closed the road to Paradise during the winter of 1942-43 and for every subsequent winter until the end of the war. In 1945-46, the first winter after the war ended, the road was reopened in March and the Paradise rope tow was fired up again for spring skiing. The decline of skiing Skiing on Mount Rainier never returned to the level it had reached before World War II. With competition from growing ski areas at Mount Baker, Stevens Pass and Snoqualmie Pass, RNPC consistently lost money on winter operations at Paradise. The Park Service shifted attention to Cayuse Pass, near the east edge of the park, installing rope tows there in the late 1940s. (Cayuse never became very popular with skiers.) In the fall of 1949, RNPC declared that it was ending winter operations at Paradise. For the next four winters, the Park Service closed the road above Narada Falls, the rope tows were mothballed, and no overnight accommodations were available. The dream of big-time skiing on Mount Rainier reached a turning point in 1954. Local merchants who wanted the road to Paradise open year-round joined with the Automobile Club of Washington to push for major expansion of the ski area. They won support of Washington Governor Arthur Langlie and his aide, Roger Freeman, a skier and former member of the Mountaineers. The centerpiece of the plan was an aerial tramway with its start at Paradise and its terminus anywhere from Panorama Point to Camp Muir, depending upon the enthusiasm of the proponent. The Auto Club was determined to wrest Mount Rainier from the “sole use of a few naturalist societies, bird watchers, and mountain climbers” and return it to “the people.” Controversy over the plan peaked in August 1954, when Governor Langlie, the Auto Club, and the Mountaineers held public meetings on the issue in Seattle. NPS Director Conrad Wirth opposed the tram and recommended against it to Interior Secretary Douglas McKay. Wirth argued that the very idea of the national parks was at stake. Ultimately, McKay sided with Wirth and rejected the proposal. In a conciliatory gesture, Wirth said that the Park Service had no objections to construction of a T-bar lift at Paradise which could be erected in winter and removed in summer. Public demand led to reopening of the Paradise road during the winter of 1954-55. A consequence of the tramway battle was that skiers began searching for a resort location outside the park. The effort initially focused on Corral Pass, northeast of Rainier, but soon moved two valleys to the south, to Silver Creek. In 1962-63 the Crystal Mountain ski area opened there, relieving development pressure on Paradise and siphoning interest from the nearby Cayuse Pass ski area. By 1972, four rope tows and a pomalift operated at Paradise in winter. But as historian Linda Helleson wrote at the time, “As winter sports grow, each year Paradise becomes less and less of a ski area.” The tows were removed for good in the mid-1970s.

Back to the future Although Paradise faded as a downhill ski area, its importance as a mecca for backcountry skiers has endured. By the 1970s, when the lifts were removed, ski touring was seen as the future of skiing at Paradise. In the past twenty years, backcountry skiing has exploded throughout the United States. But at Mount Rainier, the sport has been stunted by access problems. Paradise has no overnight facilities in winter, making backcountry skiing almost entirely a day-use activity. The viability of Paradise as a day-use ski area requires consistent (or at least predictable) road access. During the past decade, winter access through the Longmire gate has become slower and more erratic. This is largely due to a policy of completely clearing the road and parking lots before opening the gate. In past decades, the policy was to open to several intermediate points, including the Paradise lower lot, as soon as they were plowed. When skiers have to wait at Longmire until 10 or 11 a.m. (or later) before driving to Paradise, they begin looking for other destinations. The current Mount Rainier National Park management plan proposes to replace some private vehicle use in the park with public shuttles. The effect that this policy will have on winter access by skiers is uncertain. Precedence in other national parks suggests that private vehicle use is likely to be further deemphasized in the future. Skiers are justifiably concerned about more restrictions, but the transportation plan may provide an opportunity. If shuttle service could be integrated with plowing operations, it might be possible for the Park Service to run “early bird” shuttles to Paradise before parking for private vehicles is available. Since shuttles require no parking space and can coordinate with plowing crews, it might be possible to improve skier access to Paradise while reducing the number of private vehicles, a win-win situation for both skiers and the park. This crucial access question will determine whether Paradise, the birthplace of recreational skiing in the Cascades, meets the future as a vital center for winter skiing or a nostalgic backwater. As I climbed toward Mazama Ridge during our March 2009 celebration wearing antique skis and tweedy clothes, I tipped my hat to Milnor Roberts and his friends a century before. Away from buildings and cars, our little group experienced the stillness that haunted this valley before skiers ever entered it. The ski lifts are now silent, the race-day crowds have departed, and the underground city is no more. In their place we found the sigh of the wind, the swoosh of running skis, and the call of friendly voices. One hundreds years later, it’s still Paradise. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Continued <<Previous | 1 | 2 | 3 | Next>> |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ©2009 Northwest Mountaineering Journal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Site design by Steve Firebaugh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||