|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

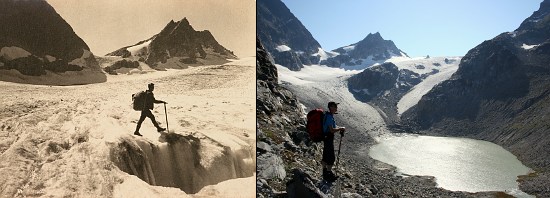

n August 9, 2009, Craig Luebben and Willie Benegas, both experienced alpinists and mountain guides, were climbing from the Taboo Glacier onto the SE Face of Mount Torment to begin the Torment-Forbidden Traverse. As Luebben was attempting to bypass remnant ice hanging above a bergshrund, a block of ice broke loose and sent him plunging into the chasm below. Benegas administered first aid and called for a rescue, but Luebben died from trauma before he could be moved. Jason Schilling and I had previously made plans to attempt the traverse, and we decided to continue despite the recent tragedy. It was with some trepidation that we crossed the Taboo Glacier, especially when the only way to overcome the gaping bergshrund was to pick our way over a hollow bridge of ice blocks. I wondered if these blocks were some of the very ice that had broken loose below Craig’s feet. Finally, we made it safely across the Taboo Glacier and onto Torment’s South Ridge. Glad to be back on rock and with anticipation for the ridgeline we could see above us, we climbed toward the summit. We would soon discover that we had underestimated the melted-out state of the classic traverse. An increased technical challenge There is no doubt that the glaciers in the North Cascades are shrinking, along with most of the other glaciers in the world. The simple reason: summertime melting exceeds the wintertime accumulation, due to a general trend of global warming. (Whether this global warming is the result of a natural climate cycle or to anthropogenic influences is beyond the scope of this article.)

While glacier recession has a myriad of environmental impacts — water supply, basin erosion, loss of a special component of the Cascades — it also has consequences for alpinists. Several climbs in the Cascades entail traveling across glaciers, either on the approach or as part of the route itself. Bare ice, bergshrunds, moats, crevasses, and unstable ice seracs have begun to present more challenges. Accompanying these are loose rock and steep slopes being uncovered around the edges of the shrinking ice masses. Moreover, these difficulties are encountered earlier and earlier in the summer. My parents never knew a bergshrund existed near the summit of Mount Challenger, but in recent years it has become a wide chasm that is at times impossible to cross. Some classic routes of the North Cascades have been affected by glacier recession; for example: the broken up state of Shuksan’s Price Glacier, the moat problems on the approach to the NE Buttress of Goode, the open crevasses on the Mustard Glacier below the North Buttress of Terror, and deteriorating ice exposing an unstable slope on the north side of the Torment-Forbidden Traverse. For many routes, the result has been an overall increase in technical difficulty. Approaches and traverses often take more time and become more involved as climbers search for ways to navigate the new cruxes. Many routes are now only feasible in the early season. With gaping cracks, deep moats, collapsing snow bridges, falling seracs, melt-induced rockfall, and bare ice, glacier recession has also increased the hazard of glacier travel. The deadly result of the collapsing moat on the Mount Torment’s Taboo Glacier is a tragic example. Nowadays, a mountaineering adventure into the North Cascades usually involves considering the condition of the route’s glaciers and planning accordingly. The impact on route descriptions

Climbing guides (or the rate at which climbers buy updated guides) to the North Cascades have not been able to keep up with the rate of glacier recession. Granted, there is no route description that is good for every condition at every time of year, and climbers can expect glaciers to open up towards the end of the season. Nevertheless, many descriptions are outdated as to new challenges caused by the shrinking glaciers or as to the best time of the season to attempt certain routes, which seems to become earlier each year.

Another consideration is the growing number of route variations that have yet to make it into the popular guidebooks. While many route descriptions do in fact mention the potential for late-season cruxes and hazards on the glaciers, a general lack of advice towards potential bypass options suggests that the challenges can be overcome by those who possess adequate alpine skills. But more and more this is not the case, especially in late season when the cracks are becoming too wide or the conditions too unsafe to reasonably attempt. Even the most skilled alpine climbers would not be prepared to lower into Challenger’s gaping bergshrund and climb the overhanging ice on the other side. Fortunately, in the case of Challenger, there is a viable bypass route along the ridge to the east. This route variation is likely to become the standard route. While most climbers do not want to follow a roadmap to the summit, they usually like to be aware of the possible and popular route options. However, climbing guides cannot be blamed for outdated descriptions. This is a problem inherent to the static nature of printed route descriptions and the dynamic nature of glaciers. It is not realistic to assume that guidebooks can keep current with each and every change in the thousands of routes in the Cascades (or anywhere else, for that matter). And even if they could, there are often several years between editions (during which the glaciers continue to recede and the routes continue to change), and several more years before climbers decide to replace the guides they already own. Hence, there will always be a lag between glacier conditions and route descriptions.

Perhaps the best response to the dynamic route conditions is a more dynamic form of route documentation. Online forums such as CascadeClimbers.com are already becoming popular sources of current route conditions and new route variations. This could foreshadow a trend toward online counterparts to the popular guidebooks that will keep track of corrections and updates for each route. Online guides would be an effective way to keep up with the changing glaciers. In light of the recent trends of glacier recession, the most important factor is for climbers to be aware of the changing conditions in the North Cascades, and recognize that a static route description might not always be representative of the route ahead. Relying on an outdated route description for planning and executing a trip can present issues of both success and safety. All it takes is one look at the NE Glacier on Mount Formidable to realize that Beckey’s "Now climb the glacier" statement (CAG) was written for a glacier that was much different than today’s. Instead, climbers can embrace the challenges of negotiating new cruxes and finding new route variations. It is all part of the challenge of the North Cascades. A Not-So-Moderate Torment-Forbidden Traverse Jason and I stood on the summit of Mount Torment, enjoying the spectacular views and gazing at the rugged mile that stretched between us and Forbidden. The Torment-Forbidden Traverse is considered one of the classic and most aesthetic alpine routes of the North Cascades. The traverse stays as high as possible; for the first half-mile it follows the upper extents of the glaciers high on the north side, and for the second half-mile it maintains breathtaking exposure right along the rocky ridgeline. The views from virtually every point on the route are stunning. To the west are Baker, Shuksan, and Eldorado; to the east are Boston, Goode, and Sahale; and to the south are the peaks of the Ptarmigan Traverse. Guidebooks classify it as a moderate route, where the technical difficulty never exceeds 5.6.

As soon as we left Torment’s summit, Jason and I found the mile-long traverse to be much more than a moderate undertaking. Granted, we were attempting the route at the end of an unusually dry and warm summer in the Cascades, where many of the glaciers were riddled with cracks and bare ice, perhaps in their most melted states ever. Going into the trip, Jason and I looked forward to the extra challenge of late season glaciers, but even so we were surprised at the difficulties we encountered on the first half of the traverse. The start of the Torment-Forbidden Traverse entails gaining the glacier just northeast of Mount Torment. When we faced a bergshrund too wide to swing across, we had to rappel into the gap between the ice and rock, which was fortunately only a few feet deeper than the length of our doubled rope. The only way out of this cold and dark chasm was to chimney between the ice and polished rock, desperately trying to avoid slipping into the narrowing gap below. Once on the surface, we reveled in the exhilaration of belaying over thin snow bridges, rappelling over gaping cracks, and scooting along the top edge of the glacier. Finally, we regained rock on the other side.

The historical crux of the Torment-Forbidden traverse is the crossing of a steep ice/snow slope at the end of the first half-mile. Beckey’s description in his ubiquitous Cascade Alpine Guide mentions that the snow is “steep” and that there is “often a shrund” towards the end of the slope. This is likely the case in June or July, but the sight that we encountered, besides its steepness, resembled almost nothing of the route description. The bergshrund no longer existed. All that remained was a thin layer of rock-hard glacier ice. Sections of the ice were strewn with dirt and rock that had previously been held back by the glacier. This would be a crux indeed. Instead of attempting to cross the hazardous wasteland, Jason and I decided to stick to the ridge high above the slope; this route variation, if it turned out to be feasible, would maintain the spirit of the ridgeline traverse. Fortunately, we found the rock on the ridge to be good, the climbing fun and moderate, and the exposure exhilarating. The only disadvantage of this route variation is that the ridge cliffs out, which forced us to make a couple of rappels to some grassy ledges on the south side. These ledges led us easily right back onto to the standard route. This aesthetic ridge variation will likely become adorned with rappel slings as the steep north side ice melts into nonexistence. From the grassy ledges on the south side, the rest of the traverse to Forbidden was indeed a moderate (and always classic) route. In the end, Jason and I agreed that the difficulties we faced on the first half of the traverse ultimately made the trip more memorable and rewarding. Since glacier recession is likely to continue, we may as well revel in the added challenges that reinforce the rugged nature that defines the North Cascades. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| <<Previous | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ©2010 Northwest Mountaineering Journal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Site design by Lowell Skoog | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||