|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

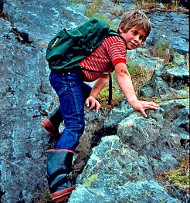

As long as I can remember, my father had a passion for the outdoors, especially the North Cascades. He and his network of hiking partners got out nearly every weekend, often to plant fish in alpine lakes as members of the Trail Blazers (NWMJ 2006). Eventually, planting fish evolved into a desire to explore the glaciers and peaks above the high lakes he came to plant. Along the way, no doubt influenced by legendary Bulgers like John Roper and Silas Wild, my dad became interested in the Bulger Top 100, a list of Washington’s 100 highest mountains. Like many young boys, I wanted to be just like Dad. While accompanying my father and his crew on some of their smaller adventures, I would hear them talk about the Top 100. Even as a youngster, this fascinated me. What could be neater than climbing the 100 highest mountains around? I was captivated. As I grew older, I was allowed to join my dad and his climbing partners on successively harder trips. At the age of nine, I summited my first Top 100, Black Peak (8,970ft, #17 of 100). Two years later I summited Silver Star Peak (8,876ft, #24 of 100). At age twelve, I summited Mesahchie Peak (8,795ft, #28 of 100). The towering views of jagged peaks and cascading waterfalls that I glimpsed from those summits left an indelible impression upon me. I formed a bond with rock and ice not unlike the bond my peers formed with their video games and action figures. But as their games and toys were lost, broken, or put aside, my passion for the mountains only grew stronger.

Fast forward to 2006. On October 21 of that year, I finished the Bulger List on Windy Peak in the Pasayten Wilderness. Although it was satisfying for me to complete the list, it was even more satisfying for me to pursue it. Throughout the time I spent working on the list, I got to see parts of the Cascades I otherwise wouldn’t have thought about visiting. I enjoyed having a finite set of objectives to choose from each weekend, and I enjoyed a certain sense of vindication when it came time for me to cross a peak off the list on Monday morning after a successful climb. Completing the list left me feeling a bit empty—I needed a new challenge. That challenge came in the form of the Top 100 x P400 list. This new list, a variation of the original Bulger List, used different criteria to determine the top 100 peaks. One of the summits on this list is Lincoln Peak, a rugged, seldom-climbed peak in the Black Buttes on Mount Baker’s SW flank. It is said that the original Bulgers nixed Lincoln Peak from their 100 highest list because they were scared of it. For some sick reason, this intrigued me. Like many climbers, I enjoy challenging myself, and I think deep down I take some sort of pride in doing things that others find scary or dangerous. It helps feed a sense of adventure and adrenaline that I feel compelled, on some carnal level, to seek out. It was this sense of adventure that interested me in Lincoln Peak, and thus, my obsession with the Black Buttes began. Like the original Bulgers, I too was initially scared of Lincoln Peak. Looking through aerial photographer John Scurlock’s photos, I was horrified by the impossibly steep snow and giant cliffs that guard its flanks. There is no mystery about why Lincoln doesn’t get climbed much—because it’s intimidating and dangerous. For that same reason, I was drawn to it, and became highly motivated to climb it. I spent two attempts on Lincoln Peak before I successfully reached the summit. On the first attempt, Paul Klenke, Fay Pullen, Mike Collins and I got within 500ft of the summit before turning around due to a lack of time. Darkness was descending upon us after climbing cautiously all day on steep, soft, rotten snow over crumbly, volcanic rock. Having already climbed through the crux, we just didn’t have enough time to finish the route and descend before dark. On the next attempt, I returned with Mike Collins and Sean Martin and ended up retreating from the exact same spot due to heavy snowfall and worsening avalanche conditions. Sean would have been knocked off the mountain by a loose snow avalanche had he not anchored into a rock twenty seconds before it showered his backpack with debris. On that attempt, we barely escaped with our lives, and at the time I swore off all future attempts. Time has a way of dulling bad memories though, and it wasn’t long before I was planning my next trip up the Middle Fork of the Nooksack River. Lincoln has only one known route, and success on the climb is ultimately determined by conditions. In dry conditions and with a lack of snow, one is forced to climb loose, crumbly, conglomerate rock. With heavier snow cover and direct sunlight, the conglomerate is snow-covered, but the sun loosens rocks and ice above, and the route is constantly bombarded by falling debris. The route faces SW, so what appear to be solid, excellent conditions at the beginning of the climb may deteriorate into dangerous conditions in the mid-day sun. Despite all this, in June 2008 I once again headed up the Middle Fork Nooksack Road with Paul Klenke, Fay Pullen, and Sean Martin to make my third attempt on Lincoln Peak. This time, each member of the party had climbed through the crux gully at least once, and we all knew what it was going to take to finally succeed. Thanks to a strong group effort, we summited Lincoln that day. It was rewarding to ultimately achieve a goal that took a great deal of perseverance and commitment. After summiting Lincoln Peak, I swore off returning. As far as I was concerned, I was done with the peak. A visit to John Roper’s website (www.rhinoclimbs.com) suddenly changed that for me. There, on his Top 100 page, is a photo of Lincoln Peak taken from the summit of Colfax. Just below the summit of Lincoln stands a seemingly impossible spire of crumbly conglomerate he calls Assassin Spire (a name Roper coined on his first climb of Mount Baker in 1967). A little blurb below the photo says, “Lincoln Peak 9080+ from Colfax Peaků Note Assassin Spire to right. It’s NBC”. I e-mailed John and asked him what “NBC” meant, and he wrote back promptly with the answer: Never Been Climbed. Scouring the internet for photos, I typed “Assassin Spire” into all the major search engines. Nothing. It wasn’t until I searched John Scurlock’s online photo gallery that I found any images of the obscure peak. For those who aren’t familiar with John Scurlock’s photography, his website is a goldmine of information for climbers. He has an amazing number of high-quality photos from all over the Cascades and beyond. His web gallery is the single greatest resource for new route research that I can think of, and several Northwest climbers (myself included) owe a debt of gratitude to him. Scurlock’s aerial photo of Assassin Spire didn’t reveal a feasible route up it. It wasn’t until I asked John to fly over it and get some more definitive photos that a plausible route came into view. I was unaware at this point that some very competent and experienced parties had been making attempts on the spire but had so far come up short. On February 15th, 2010, Scurlock did a fly-over and captured a very telling photo of the spire. From the photo, I spotted what looked to be a practical route up to the summit. I contacted my new friend Daniel Jeffrey and informed him of my plans. He was eager to be a part of the program, despite not knowing much about the Black Buttes other than where they were located. At that point, aside from some ice climbing in Leavenworth, Daniel and I had shared only one short day-climb together—Chair Peak’s North Face and NE Buttress—earlier in the same week. I was a bit hesitant to embark on such a serious climb with someone I barely knew, but I couldn’t round up any of the usual suspects on such short notice. Besides, Daniel and I seemed to mesh well together, and he definitely had the technical ability, so I felt comfortable having him join me. As far as Daniel and I could tell, the conditions for an ascent on Assassin Peak looked favorable. The forecast called for clear skies and cold temperatures through our planned summit day, and there had been little recent precipitation. On March 5, under clear skies, we approached from the Middle Fork of the Nooksack River via Warm Creek to Marmot Ridge. After an approach of five miles and 3200ft, we camped near 6200ft on the Thunder Glacier. From camp, 2500ft of steep snow and ice remained between us and the untouched summit. For the first time, we could plainly see the hanging glacier resting like a puma in the grass, waiting to pounce on any unsuspecting victim in its path. Giant cliffs of snow and rock adorned its flanks, and ice flowed down its walls like frozen tears. It was hard to sleep that night in anticipation of the climb, so when the alarm went off at 3 a.m. the following morning, I was still groggy. Van Halen blared from the iPhone as we brewed up a liter of coffee to share. By 4:30 a.m. we were donning our packs and heading across the Thunder Glacier into the unknown. As we plodded across the snow, I was silently giddy that we were finally on our way. I wanted to remain calm and focused, but I couldn’t suppress the cacaphony of thoughts racing through my brain. Faint moonlight illuminated the snow just enough to see the spire’s ominous silhouette as we neared the approach gully. An hour after leaving camp, we were standing at the base of an impressive ice curtain, the first of many obstacles on our way to the summit. Above we could see two 25m pitches of vertical water-ice, separated by a ledge, leading up toward the unknown. We weren’t expecting vertical ice from the aerial photos, and we wondered about our rack selection. We brought only six ice screws between us, expecting it to be mostly a steep snow climb. We debated whether we should try to find another route, but I knew from looking at the photos that there were no better alternatives. I led up the first 25m on brittle ice. Large chunks of ice were breaking off with every swing of the tool. It took several swings to get a solid stick in some places. There were bulges that overhung for a short distance, and with multiple swings for each placement it was very challenging climbing for me. About a third of the way up, after placing two screws, I finally got a no-hands rest with one foot on gently sloping rock, and my other foot with two front-points in vertical ice. Two-thirds of the way up, I had used all but one screw. I climbed another 10ft or so and placed my final screw. I was still 15ft below the top, and I wasn’t comfortable running it out with one more bulge above me, so I back-cleaned a screw and lowered down to let Daniel finish the pitch. Daniel climbed to where I had left off and finished the remainder of the pitch to a belay on a snowy ledge halfway up the ice curtain. From Daniel’s belay ledge, I led up another 20m on vertical water-ice followed by some steep snow-ice. Parts of this were very thin, and I bottomed out some 16-cm screws in the shallow ice. This pitch reached the crest of a narrow buttress where I buried a picket and belayed Daniel up. The buttress led to a 55-degree gully, which we followed up to the hanging glacier. The hanging glacier lies in the middle of an intensely alpine amphitheater of rock, ice, and snow. Steep walls of rock and ice reach toward the sky in all directions. The bottom edge of the hanging glacier forms an enormous serac that threatens the base of the spire. Fangs of ice drape the walls like tapestries in a cathedral. There are few other places in the North Cascades that can match the spectacle of the hanging glacier amphitheater on Assassin Spire in winter. We traversed across the hanging glacier above the serac just as sunlight began to illuminate the cliffs above us. Daggers of ice and balls of snow came whizzing out of nowhere with thunks and whoomps, some glancing off our helmets. We hurried up and across the glacier and gained a 45-degree couloir leading to a feature I dubbed “John Wilkes’ Tooth,” a huge pinnacle of rock separating two ice gullies below the summit snowfield. The gully on the left started with a vertical, 15m fang of ice of which 5 meters had broken off at the bottom, making it impossible to climb. Instead, we opted for the 55-degree snow-ice gully to the right of the Tooth accessed by a 20m, mostly-vertical ice step. Daniel led this pitch and belayed me up on a deadman picket. From here, we climbed three rope-lengths of 55-to-60-degree snow to the summit, finishing on a beautifully exposed snow arete overlooking Lincoln Peak’s NW flank. We were elated to be standing where no human had ever been. We took time to savor the beauty surrounding us and congratulated each other on a job well done. We spotted a team of skiers at the col between Colfax Peak and Mount Baker who apparently heard us whooping and hollering and they hollered back. We were buzzed on the summit by an EA6B Prowler military jet that circled around us twice and tipped his wing on the second pass. Later we learned that local climber Steve Trent was on board, checking out the route for a possible attempt later in the month. Steve, Dallas Kloke, and Scott Bingen had made a previous attempt on the spire in 2004, but were turned back by rotten rock. We relaxed on the summit for a full hour, relishing the beauty and ruggedness of our surroundings and savoring our hard-earned victory. Eventually we began our retreat, leaving our obsessions behind, and turning our backs toward a place that neither of us will ever forget. |

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ©2010 Northwest Mountaineering Journal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Site design by Lowell Skoog | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||