|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

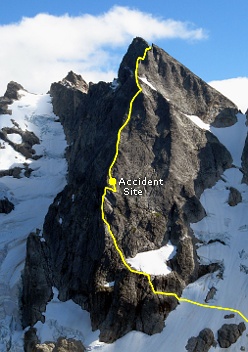

uring the summer of 2008, Donn Venema, Steph Abegg, and I planned to climb the North Buttress of Mount Terror during an enchainment of the Northern and Southern Picket Ranges. The 2500-ft buttress was first climbed by John Stoddard, solo, in 1984. Our attempt was abandoned after a storm pinned us on the snowy summit of Mount Fury for three nights. I had stared at Terror’s striking buttress during the last two days of that trip and I fantasized about it during the long rainy months of the following winter. On July 2, 2009, Donn, Steph and I were joined by Steve Trent for seven-day climbing trip in the Southern Pickets. While we had never climbed with Steve before, he was veteran of the Pickets and other areas of the North Cascades and made a welcome addition to our party. We hiked to a camp in Terror Basin and completed ascents of Inspiration Peak, Mount Degenhardt and The Pyramid. On our third day, we moved camp from Terror Basin to Crescent Creek Basin and celebrated the Fourth of July with whiskey and sparklers. We planned to tackle Terror’s North Buttress, the primary objective of our trip, the following morning. The Fall Leaving our camp in Crescent Creek Basin with light day packs, we traversed for an hour across snowfields with the Southern Pickets looming above us. Early morning light bathed Mount Triumph and Mount Despair as we cramponed up the couloir to Himmelhorn-Ottohorn Col. Happy to break out of the shade, we rappelled onto the sunny slopes of Mustard Glacier. We glissaded down the glacier and soon caught a glimpse of the buttress. After wending our way through ice falls and polished slabs for an hour, we left the glacier for the North Face itself. We scrambled over fourth-class terrain and roped up at the base of a large perched snowfield. Steve and Steph climbed ahead of Donn and me. Although this was only our second season climbing together, Donn and I had bonded effortlessly on last year’s trips in the Pickets, and I was excited to have him lined up as my partner for a good portion of my summer climbing vacation. We worked up and left over easy terrain to reach the crest of the buttress. Clean white gneiss predominated on the lower section on the climb, and I was thrilled to be climbing solid rock in a range that has a mixed reputation for rock quality. At around 10:30 a.m., as Donn and I were simul-climbing about a third of the way up the buttress, the sound of a large falling rock shook me from my climbing reverie. An eerie silence followed, accompanied by the acrid smell of rockfall. We were below Steve and Steph and separated from them by a prow of the buttress. Steph’s frantic shouts to Donn were indecipherable to me as I waited anxiously on a crumbly ledge. I held my breath as Donn relayed to me that Steve had fallen and was badly hurt. Steph was the closest to Steve and can best describe what happened:

A climber’s nightmare was unfolding. I could hear Steve’s moans as I inched my way along the rotten ledge to Donn and his belay anchor. I reached Donn at a near-crawl, legs shaking, and declined the opportunity to lead the low-fifth-class terrain to Steph and Steve. I reminded Donn to breathe and move slowly as much for my reassurance as for his. I asked him to get Steve’s heart rate and put warm clothes on him immediately. Once Donn had set up a belay I climbed slowly up to my partners and assessed the situation. A large bloodstain marked the wall just above the ledge where Steve was slumped. His face was gashed and swollen, and clots of blood were spattered on his helmet and the ground at his feet. Donn and I at first mistook these clots for brain matter and the look we exchanged revealed our fears about Steve’s chances of surviving the day. He was missing his right climbing shoe and his left thigh was incredibly swollen, indicating a broken femur. I was soon promising to myself that if I made it off of this mountain I would spend the rest of my two-month vacation bird watching and cragging. The “flip-flops and bolts” that Donn joked of during times of alpine hardship were more appealing than ever. I assessed Steve’s condition following the steps drilled into my head during ski patrol training. He was in and out of consciousness, asking the same questions each time he awoke. “What happened?” “You fell, Steve.” “How did I fall?” “We think a rock broke away from the mountain as you pulled or stood on it.” “Oh…” Then, “What happened?” He had no apparent core injuries or spinal cord damage, but had a deep gash on his head, which had stopped bleeding. The biggest concern was his broken femur. There was minimal blood on the pant leg of the left thigh, but blood was dripping slowly down his leg onto the ground. This was a troubling sign. But what could we do if we cut his pants open and learned that the fracture was compound? We didn’t have the proper gear to apply traction to the femur. So the best we could do for Steve was bandage his head and make him as warm and comfortable as possible. While Donn and I attended to Steve’s injuries, Steph climbed to a ledge 20 feet above us and built a more secure anchor. Steve and Steph had been climbing on a doubled half-rope, and one strand had been nearly severed during the fall. Only the fact that the rope had been doubled, leaving the other strand intact, had saved Steph and Steve from falling off of the mountain. Donn cut the rope in half at the exposed core so that Steve and I could tie into the anchor on separate strands. We formed a plan: Donn and Steph would continue up the buttress in hopes of making a 9-1-1 call from the summit while I would stay with Steve. It is neither a common nor an easy decision to split up a climbing party, but it was the only way that we could get Steve help before nightfall. In his condition, it was unlikely he could survive a night on the mountain. This plan played to our individual strengths: Donn and Steph were faster climbers, and I knew more about first aid. A stroke of luck was that I had tossed my cell phone in my backpack that morning on the off-chance that we could get a signal at the summit to call friends and family for a weather update. However, getting a phone signal in the heart of the Pickets is by no means guaranteed, and if this failed Donn and Steph would descend to camp on the other side of Mount Terror and hike out for help. But this would take a couple of days, and time was crucial to Steve’s survival. So, after organizing the gear and giving us their extra clothing, Steph and Donn climbed out of sight. It was hard watching them go. I was left with my thoughts and Steve, tiny specks on the imposing North Face of Mount Terror. The Watch Steve was in a world of unimaginable pain. His current state was ghastly, especially the sight of his badly swollen leg. I noticed more blood dripping down his pant leg and his face was so badly swollen that he was unrecognizable. He was bundled up in two insulating jackets and was sitting on a narrow sloping ledge. His feet were resting on another ledge. The sun soon arced above us and provided us with warmth for the remaining eight hours that we spent together on the ledge, although Steve was still bundled up and shivering at times. As Steve’s nurse, I was constantly fretting over him. At first I stood on the ledge inches from him, staring at his chest to make sure that he was still breathing. I filled my time with the simple tasks of checking his heart rate, helping him urinate, giving him pain-killers, and talking to him when he was conscious and willing to converse. Although he became more coherent over the course of the afternoon, his speech and motor skills were significantly impaired from the head trauma. The bleeding on his leg had stopped, but I was still worried about it. I wanted to make Steve more comfortable, so I moved his legs onto the upper ledge, hoping the swelling would go down in his broken leg. I climbed up to the ledge next to the anchor and scoped it out for a potential bivy. Two could sit comfortably here and one could lie down somewhat awkwardly. I watched Steve doze below and wrestled with the possibility of spending the night on the mountain. Steve’s right foot fell off the ledge and the sudden pressure on his left leg jolted him awake. He moaned and grabbed his leg. “My leg is on fire,” he muttered. I down-climbed to him and propped his right leg back up and used my body to hold him on the ledge, bracing my leg against his right thigh as I knelt on the ledge below him. “You didn’t think you’d be babysitting when you woke up this morning,” he slurred. His humorous quip gave me hope that his condition was stabilizing. The afternoon was slipping by. Steve asked me to find his rock shoe so we could finish climbing the buttress. “We have to get out of here before dark.” I couldn’t help but laugh. He couldn’t even zip up his fly. He asked me about the ledge next to the anchor. How big was it? How far away? I climbed back up to the ledge, where I secured one end of a 20-foot section of rope that had been cut by Donn to the anchor with a figure eight. I attached my cordelette to the rope with a prusik knot and attached the other end to Steve’s harness. This way the direction of pull would be straight up the ramp to the anchor and he wouldn’t swing out onto the face if I dropped him before I could push up his prusik. We attempted to move and he groaned from the pain and stopped after gaining two feet. I gave up after that first try. I had asked Steve to use his good right foot to help him up the ramp. I didn’t realize until much later that he had shattered the heel on his “good foot,” rendering it as useless as his left leg. Doubt crept in again about Steve’s ability to survive an exposed bivy on the mountain. I watched the sun sink lower in the sky. Then Steve heard the chopper. I didn’t believe him at first, but it soon cruised past us and headed toward Picket Pass before doubling back. “Donn and Steph must have speed-climbed the rest of the buttress,” I thought, as I frantically waved a small foam pad. They cruised by again and came back, this time slower. I flapped my arms. They circled and flew past once more, this time closer to the rock. They slowed to a hover and I could see two people in the front. I gave them a weak two-fingered wave. They waved back and were gone. I desperately hoped they’d come back, but my heart sank with each passing minute. A half-hour passed and Steve made another suggestion that we move up to the ledge near the anchor. “How big is it?” He asked again. I explained that it was bigger than our present ledge and flatter. “Was it below or above the anchor?” His renewed critical thinking was encouraging. I decided then that we would have to get up to the ledge, even if it took the remaining few hours of light. Double-checking our anchors, I asked Steve if he was ready. In a minute, he said. This went on for some time. He simply forgot that we were trying to climb up to the ledge. He tried to stand up with my help and said he felt like he was going to puke. I gazed out at the vista while Steve lost his concentration and dozed. The views that day were stunning, across the cirque to the southern slopes of Mount Fury, down to Mustard Glacier, and west to Perfect Pass. This could be the best place to ever be stuck, in good weather at least. “Steve, are you ready to move?” I asked again. I felt that getting up to the ledge would enable him to lie down and even elevate his leg. Steve pushed himself up with his hands as I grabbed the rope and pulled. As soon as there was slack in the rope I’d slide his prusik up to secure his progress. There were several resting spots on the ramp up to the ledge, just big enough for him to sit on. He only once complained of the pain. I’d given him two more painkillers before we started up for the ledge. We inched our way up the ramp. I had to hold the rope with my right hand and teeth to release enough tension to move the prusik up with my left hand. We were moving slowly but with determination to reach the ledge. We were within two feet when the helicopter appeared again. This time a man dangled from a line attached to its base. I waved my arms and the co-pilot waved back. The helicopter hovered 200 feet above us and slightly out from the rock. Climbing ranger Kevork Arackellian inched closer to us on the line, which was attached to him via a chest and waist harness. Then he landed on a ledge adjacent to us and moved slowly towards Steve. At the mercy of a strong wind and the jerking helicopter, he worked hard to clip Steve into his harness. The snap of the carabineer clipping into Steve’s harness was a wonderful sound. “I have to cut this rope” Kevork shouted as he pulled out his knife. He cut the prusik and Steve’s second rope anchor and was preparing to depart. “Hey you have to cut this one,” I yelled frantically over the roar of the helicopter, pointing to Steve’s initial rope anchor. Kevork fumbled for his knife again and cut the last line that held Steve to the mountain. He then unstrapped a large backpack and handed it to me. “There’s a radio in there,” he shouted. Then they were both gone. |

|

|||||

|

Continued <<Previous | 1 | 2 | 3 | Next>> |

||||||

| ©2010 Northwest Mountaineering Journal | ||||||

| Site design by Lowell Skoog | ||||||