|

| Carl Skoog traverses Stetattle Ridge in the North Cascades in 1985. |

|

[Reprinted from the 1983-1990 Mountaineer Annual - with some photo

substitutions]

Skiing the skyline—starting at point A and skiing to point B, never retracing your tracks, never knowing quite what you will find over the next pass—that is the appeal of high route skiing. In Europe, high ski traverses have been an important part of alpinism since 1897, when Wilhelm Paulcke led a party across the Bernese Oberland. In North America, Orland Bartholomew skied the length of the Sierra Nevada alone in the winter of 1929.

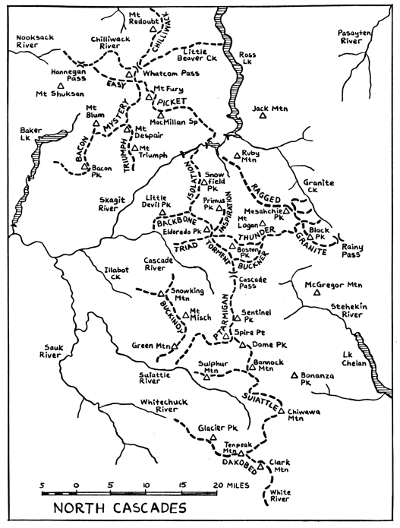

Yet in the Pacific Northwest, high route skiing is just emerging from infancy. This can be explained in part by late development of mountaineering here. It can further be explained by the unique characteristics of our Northwest mountains. The Olympics, and especially the North Cascades, are wild country. There are no alpine huts; many valleys are unroaded. The window of opportunity for a ski traverse, when stable weather coincides with a solid snowpack, is short, sometimes only a few weeks in May or June. The terrain is rugged and complex. In many places, the only practical route traverses an alp slope or double cirque, where cliffs above threaten avalanches and cliffs below await a slip. All these factors have limited Northwest ski mountaineering mostly to ascents and descents of individual peaks. They make ski traverses here especially challenging. Since 1980, a small number of ski mountaineers have responded to this challenge, exploring a network of over 300 miles of high country in the North Cascades and Olympics. They have discovered that spring ski traverses yield rewards not available in summer. Routes scarred in August by boots or careless camping are pristine in May when buried by snow. There are no cairns to follow, so a ski party feels as though it is exploring the route for the first time. Snow and wind sculpt the terrain into elegant and ephemeral shapes. Even country that is familiar on foot seems new when viewed through a skier's eyes. The Routes As the classic North Cascade high route, the Ptarmigan Traverse was an early target for ski mountaineers. The first attempts to ski it, by Steve Barnett and friends, showed clearly the problems that later parties would have to overcome. With Bill Nicolai, Barnett set out for the Ptarmigan in May, 1977 after a series of heavy storms. On the first day they reached the crux of the route, an avalanche slope between Mixup Arm and the Cache Glacier that was warming dangerously in the mid-day sun. They camped to wait for cooler temperatures the next morning. Later that afternoon and the following day they watched avalanches repeatedly plunge off Mixup Peak, sweep their route, and thunder over cliffs to the valley floor below. They had little trouble deciding to retreat.

The following June, Barnett returned with Dave Kahn and Mark Hutson. They got past the crux avalanche slope this time, but were trapped by fog and drizzle in the middle of the traverse. The bad weather lasted longer than their food supply, so they had to bail out via the South Cascade River. The ensuing bushwack was so awful that Barnett didn't return for four years. Intrigued by one of Barnett's slide shows, Brian Sullivan convinced Dan Stage and Dick Easter to attempt the route in 1981. Their successful June traverse was uneventful by comparison with the earlier attempts. According to Sullivan, the main obstacle on their five-day trip was a thinning snowpack, which forced them to walk several sections. [Note: Later contacts indicate that Dick Easter was not on the 1981 ski trip. He had previously done the traverse with Sullivan on foot.] In a range as rugged as the North Cascades, a skier needs to minimize weight in order to negotiate the terrain. This means that a party is unlikely to carry enough food to finish their route if they have to wait out a storm. This has led to a style of travel best described as “blitz skiing.” The party waits in town for a break in the weather, continuously rearranging vacation schedules and banking extra work hours. As soon as the weather breaks, they bolt for the mountains, packing as many peaks and ski runs into the trip as possible before collapsing at their cars at the end of the traverse. Gary Brill, Mark Hutson, Kerry Ritland, and I used this approach to ski the Ptarmigan in June, 1982. After each lunch or dinner stop, we'd scramble up another summit or take another ski run, eventually climbing four peaks and making side-trips to ski four glaciers in a quick three-day trip. When the weather unexpectedly held, Brill headed straight out again with Brian Sullivan and Joe Catellani. They spent five days skiing the Dakobed Range from Glacier Peak to Clark Mountain, carving turns in their shorts while Puget Sound was baking in the 90s. In March 1983, Brill, Sullivan, Hutson, and I skied from Snowfield Peak to Eldorado by traversing around Isolation Peak and climbing onto Backbone Ridge. The “Isolation Traverse” pointed out the disadvantages of setting out too early. Short days, soft snow, and unsettled weather make March and April trips problematic. We spent a day tent-bound in a storm before hurrying toward the Cascade River on our fifth day out.

Eldorado Peak has been a ski mountaineering destination for many years. Only recently, however, have skiers ventured far from the peak onto the surrounding icefields. Brian Sullivan and Greg Jacobsen explored the region NE of Eldorado when they skied the “Inspiration High Route” to Primus Peak in May 1984. John Dittli and Jeff Clark visited the SW high country when they skied the Triad High Route from Hidden Lake Peak to Eldorado in July 1986. Finally, my brother Carl and I explored the NW comer of the region in June 1990 when we skied from Little Devil Peak to Eldorado via Backbone Ridge. This area is seldom visited. Of the three “Backbones” we climbed along the way, only one had a register and ours was only the fourth entry. The experience gained on these trips led to bolder and more ambitious plans, culminating in May 1985 with a traverse of the Picket Range. My brother Carl, Jens Kuljurgis [now Kieler], and I skied from Hannegan Pass to Whatcom Pass, then plunged into the Pickets, crossing the Luna and McMillan cirques and following Stetattle Ridge to the town of Diablo. Along the way we had to scurry underneath ice cliffs, kick off avalanches and ski down their paths, and rappel with full packs to get from one ski slope to the next. We were nearly trapped high on Mount Fury when clouds closed in below us, blotting out our escape routes. It was a six-day ski trip with all the intensity of a serious alpine climb. Less nerve-wracking, but just as scenic, was the “Thunder High Route” from Fisher Peak to Eldorado Peak across the headwaters of Thunder Creek. Jens Kuljurgis, Dan Nordstrom and I skied this route over five days in May 1987. On the third day, we had a spectacular view of the north face of Mount Goode as we skied up the Douglas Glacier and nearly over the top of Mount Logan. We continued via the Boston and Forbidden glaciers and skied across still-frozen Moraine Lake before reaching Eldorado. Over time, the planning of these trips was refined to a science. By plotting the length and elevation gain of each route against the time it took, I came up with a formula that I could use to predict future trips. For example, a traverse that was 60 miles long with 20,000 feet of climbing should take 7 days, according to the formula. That was an average, of course. We were curious what might be possible by varying the style and goals of a trip. In June 1988, my brother Carl and I skied the Ptarmigan Traverse in about 21 hours by skipping summit and ski detours and traveling light. The feeling of freedom and continuous motion made us almost forget our tiredness at the end of the day.

1989 was the busiest year, when four traverses were done in a single spring. In early May, Brian Sullivan, my brother Carl, and I skied the Buckindy Traverse from Green Mountain to Snowking Mountain. Although most of it was reasonable ski terrain, this route had a trouble spot at Kindy-Buck Pass. We rappelled over a wall of cornices into a steep avalanche basin at the head of Kindy Creek. We had some nervous skiing until we could get out of shooting range of those cornices. The trip took three days. A month later, Brian, Carl, Joe Catellani, Jens Kuljurgis and I skied the Bailey Range Traverse from the Soleduck River to Mount Olympus in five days. The high point of this trip was the beautiful and exposed crest between Mount Ferry and Bear Pass. We also made a ski ascent of Mount Olympus itself. While our party was in the Olympics, John Dittli and Scott Croll, backcountry rangers out of Marblemount, skied one of the most remote sections of the North Cascades. They started at Anderson Lakes, skied over Bacon Peak to Mount Blum, then across "Mystery Ridge" to Jasper Pass, continuing to Mount Challenger. Originally planning to follow Easy Ridge to Hannegan Pass, they changed their destination to Ross Lake via Little Beaver Creek when the weather threatened. Fortunately, their Park Service connections helped them catch a boat back to civilization. Dittli, a California native, said that this six-day trip was more strenuous and committing than any he had done in the Sierras. Finally, in mid-June my brother Carl and I skied the “Suiattle High Route.” This six-day trip traversed from Sulphur Mountain to Canyon Lake, then passed Image Lake and Miners Ridge on the way to Lyman Lake basin. We skied and scrambled over the top of Chiwawa Mountain, high around Fortress, then over High Pass to the Dakobed Range and Glacier Peak. A ski descent from Glacier's summit would have iced the trip, but it was foiled when a rainstorm chased us down from Disappointment Peak. The Future The North Cascade traverses described here form a nearly continuous high route from Glacier Peak to the Canadian Border. There are a few gaps remaining, particularly the Chilliwack region north of Whatcom Pass and the “Hanging Gardens” between Dome Peak and Bannock Mountain. The section from Cascade Pass to Eldorado was probably skied many years ago.

Several of the established high routes have variations to explore. The Thunder High Route could be varied from Mount Logan to Cascade Pass by skiing through Park Creek Pass and around the south side of Mount Buckner. The party that made the first winter ascents of Mounts Triumph and Despair in 1986 skied as far as Despair, but no farther. There is an interesting section around Mount Despair that needs to be sorted out before one can connect up with Mystery Ridge. A party with adequate time and weather should try following Easy Ridge to approach or exit from the Pickets. All of these are established backpacking routes, but they are sure to be challenging when traversed on skis. The Ptarmigan Traverse is the most suitable route for one-day “sprints”, but there may be other candidates. Several of the routes could be done as fast overnight trips. So far, these traverses have always been limited to a week or less. This is a practical limit due to the narrow weather windows and the difficulty of skiing rugged terrain with heavy packs. The greatest adventure awaits a party who is willing to pack in caches in Autumn so that a traverse can be extended to several weeks. Fanatical skiers could try the routes in mid-winter. Whatever the future may hold, there is great opportunity for personal discovery in high skiing. Long traverses are just the broadest brush strokes across the canvas of the mountains. There are endless details to fill in—bowls to ski, ridges to run, glaciers to explore. The mountains will never be skied out—with every snowfall the canvas is wiped clean. This article was published in the 1991 Mountaineer Annual, which covered the years between 1983 and 1990. Starting in 1907-08, the annual was published every year through 1982, then sporadically for the years 1983-90, 1991-92, and 1993-94. Since 1994, the annual has not been published again. From 2004 through 2010, the Northwest Mountaineering Journal served as an informal surrogate for the old annual.

--Lowell Skoog

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Alpenglow Gallery |