|

The White Canvas - Ski Mountaineering in the North Cascade RangeSkis arrived in the North Cascades in the 1890s, as men began working in the mining districts of Monte Cristo and Silver Creek year-round. Skis were often the easiest way to travel between the camps in winter. As mining gave way to tourism, skiing for recreation emerged. During the summer of 1920, the last year of organized mining at Monte Cristo, an informal ski tournament was held in Glacier Basin, 2000 feet above the town. “No prizes were handed out,” wrote historian Philip Woodhouse. “The only trophy was the joy of competition.”

The opening of Mount Baker Lodge in 1927 made Heather Meadows the center of organized recreation in the North Cascades. Members of the Mount Baker Ski Club visited the area for skiing in the 1920s. Popularity grew after the state highway department started maintaining the road in winter in the mid-1930s. Rope tows were installed at Heather Meadows (today’s Mount Baker Ski Area) during the 1937-38 ski season. The first ski ascent of a major Cascade peak was made on Mount Baker by Ed Loners and Robert Sperlin in May 1930. Like the first winter climb of the mountain five years earlier, the ski ascent used Kulshan Cabin as a high camp. Kulshan Cabin was located on the northwest side of Mount Baker. On the other side of the mountain, to the northeast, was Mount Baker Lodge. Ben Thompson, a guide at Mount Baker Lodge, pioneered a high-level ski route between the lodge and the summit of Mount Baker in 1931. With Don Henry and Darroch Crookes, Thompson used this route to attempt a ski circumnavigation of the volcano in the spring of 1932. The men spent seven nights out, four nights camping on glaciers and three waiting out a storm at Kulshan Cabin. On the eighth day, they hoped to complete their loop back to the lodge, but they were instead forced by a thunderstorm to bail out down the Middle Fork Nooksack River. This adventure was decades ahead of its time, and foreshadowed the high-level ski traverses that would be established in the North Cascades more than a half-century later.

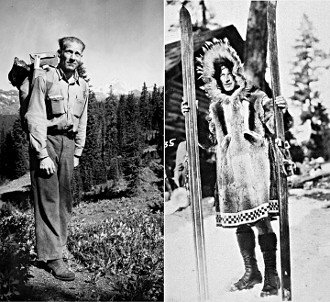

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, ski exploration in the western Cascades was spearheaded by wiry and energetic Dwight Watson. With a handful of friends, but especially ski racer Sigurd Hall, Watson scouted and made movies of areas never previously visited on skis. In 1938, Watson and Hall made the first ski ascent of Glacier Peak. That same year they explored Ruth Mountain, Eldorado Peak and North Star Mountain in the North Cascades. Farther south, Watson made first ski ascents of Mounts Hinman and Daniel, and conducted an early foray into the Goat Rocks. In 1939 he led the first summit ski traverse of Mount Baker, from Kulshan Cabin to the Mount Baker Lodge. Watson’s ski ventures were generally made in spring, when snow lay deep over the North Cascades, but weather and avalanche danger were milder than in winter. East of the crest, at about the same time, Dale Allen and Walt Anderson were making long ski trips in the Pasayten wilderness in the dead of winter.

Allen and Anderson worked for the State Game Department and U.S. Forest Service. Their duties included game surveys and patrolling for law enforcement. But their longest winter trips were made solely for enjoyment. Between the 1930s and 1950s they made trips of up to ten days in length, covering as much as 70 to 80 miles through the Pasayten wilderness in winter. Their “Pasayten Trip” ventured north from Harts Pass along the Pasayten River nearly to the Canadian border, then turned southeast to the head of Lost River, eventually reaching Winthrop via Eightmile Creek. Their “Ashnola Trip” traveled from Winthrop up the Chewuck River to the Ashnola River then traversed to Cathedral Pass and Horseshoe Basin before descending to the town of Loomis. Carrying packs of only 20 to 25 pounds, Allen and Anderson slept in forest patrol cabins whenever possible. But when necessary they’d camp out in the open, sometimes in temperatures below zero Fahrenheit. They carried no tent or sleeping pads but instead relied on an axe and backwoods skills. Stopping well before darkness, they would dig a snow trench and line it with fir boughs to sleep on. One man would sleep while the other man tended the campfire. Allen later recalled: “My partner and I, we'd team up. We’d put his little sleeping bag and mine together. I’d keep the fire up so long, then we’d change — it was just that cold — in order to get any rest. We got enough rest that way, by digging into the snow. We made it through fine.” When asked many years later why he made these trips, Allen replied, “For the simple pleasure of going, just being out in nature ... there is the beauty of the country ... just being out there.”

Following World War II, mechanized skiing in the Cascades grew dramatically, but very few skiers ventured into the backcountry. Most ski tourers west of the Cascades were members of The Mountaineers club. They repeated trips pioneered by Dwight Watson and others before the war and explored new areas as logging roads penetrated deeper into the mountains. On the east side of the range, Chuck and Marion Hessey of Yakima made ski trips into the Lyman Lake region (near the Holden mine) and the Pasayten country near Spanish Camp. Puzzled by the prevailing apathy toward ski touring, Chuck Hessey wrote in 1948: “If this range in its present unexplored (winter) state were set down in the middle of Europe, the people would go wild with joy. The Alps have been crisscrossed with ski trails from end to end for lo! these many years. Here we have made only a very small beginning — and so few skiers in this region realize that they have been born into a time and situation that will make them the envy of the future.” Hessey’s vision of skiing in the North Cascades began to be realized in the 1970s and 1980s. A new generation of skiers was attracted to the backcountry, inspired by the revival of telemark skiing. Steve Barnett and Bill Nicolai were early proponents of this style of skiing, and they recognized that lightweight telemark gear was ideal for covering long distances. In the spring of 1977 they tried to ski the Ptarmigan Traverse, the classic high route between Cascade Pass and Dome Peak.

Over the next two decades, skiers traversed hundreds of miles of high-level routes in the North Cascades. These routes typically cross “alp slopes,” moderately inclined slopes with gullies or cliffs falling away beneath them and steep summits soaring above. Skiers cross from one glacier to the next over high passes and pause to climb nearby peaks and enjoy spectacular ski runs. I participated in many of these pioneering trips, eventually skiing from Mount Baker to Glacier Peak, with side trips extending both east and west from the main divide. John Dittli and Scott Croll, backcountry rangers in North Cascades National Park in the 1980s and early 1990s, skied from Baker Lake to Whatcom Pass and traversed the Chilliwack Range to the Canadian border. Steve Barnett, Greg Knott, and friends skied several long routes in the Pasayten Wilderness, following higher and more rugged lines than those skied earlier by Dale Allen and Walt Anderson. In the mid-1980s, Steve Hindman and friends traversed the Canadian border from the east edge of the Pasayten to Hannegan Pass in an 18-day effort. Most of these trips were made in spring.

With the arrival of the new millennium, skiers switched their attention from the horizontal (skiing long distances) to the vertical (carving extreme slopes). As one of the grandest and most conspicuous peaks in the North Cascades, Mount Shuksan was an early target of these efforts. Steep ski descents were made on Shuksan’s north face (Karl Erickson and Greg Wong, 1979), summit pyramid (Steve Vanpatten and Jim Witte, late 1980s), and northwest couloir (Rene Crawshaw, late 1990s) before attention shifted to more remote peaks elsewhere the range. Since 2000, ski mountaineers have tackled dozens of airy summits in the North Cascades on skis, following routes that were traditionally used only by climbers. The list of peaks that have been tracked by skis now includes Mount Spickard, Hozomeen, Mt. Fury, Jack Mountain, Forbidden Peak, Mt. Buckner, Mt. Formidable, Black Peak, Mt. Logan, Mt. Goode, and many more. Full CircleBonanza Peak, the monarch of the range, still beckons, of course, standing far above Holden Village. There, in April 2011, a circle was closed: Jason Hummel (on skis) and Kyle Miller (on a snowboard) descended from near the top, following the route of my 1979 winter climb. On the steep face where my brother Gordy, friend Mark, and I had descended by backing down on crampons, Hummel and Miller made careful jump-turns, leaving curved tracks as the only sign of their passage. On one level, this ski and snowboard descent was light years away from the days of climbing Mount Baker from Kulshan Cabin in the 1920s. But on a more fundamental level, the North Cascades haven’t changed. Remote, lonely, with summits chiseled in snow and ice, these mountains continue to inspire awe and deliver adventure for each succeeding generation.

This essay was written for the book, Snow & Spire: Flights to Winter in the North Cascade Range, by John Scurlock, released by Wolverine Publishing in 2011. Artwork by Donald A. Smith, based on a photograph by Carl Skoog. |

The Alpenglow Gallery