|

y

knowledge of rock climbing activities in the Omak area dates back to the

early 1970s. Undoubtedly, mountaineers seeking practice rocks, or

wandering cragsmen looking for solitude poked about the cliffs before then,

but none of them published their activities; indeed, none left any written

note, old piton, nor even a tattered rappel sling that future climbers have

been able to find. We presume their visits were rare. y

knowledge of rock climbing activities in the Omak area dates back to the

early 1970s. Undoubtedly, mountaineers seeking practice rocks, or

wandering cragsmen looking for solitude poked about the cliffs before then,

but none of them published their activities; indeed, none left any written

note, old piton, nor even a tattered rappel sling that future climbers have

been able to find. We presume their visits were rare.

|

|

|

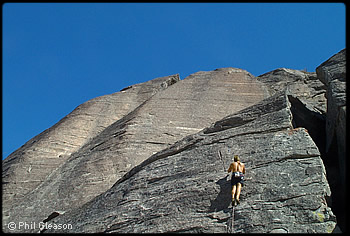

Climber on Omak Crack. © Phil Gleason. Enlarge |

|

|

In the 70s a group of Omak-Okanogan area teenagers began to explore

the rocks in their backyard. As was common with climbers of that era, they

started out hiking and scrambling, and then scoured books for techniques

that they could use to take their excursions onto more vertical terrain.

Around this time (1975) Paul Gleason from Southern California arrived on

the scene, and stimulated the “locals” with his import of techniques

learned from the Sierra Club’s programs in the ’60s in

the Los Angeles area. The active Omak clan then included Paul, John and Jim

Goss, Kurt Danison, Jerry Donner, Chuck Split, Bruce Thompson, and Rob Jeter

among others.

Typical of American climbers in the ’70s, these climbers were

heavily influenced by an expanding ecological consciousness that affected

most of us at that time. Not only with regard our earthly environment in

general, but also in the preservation and protection of the crags, a new

attitude was reaching national popularity. With an ethical system supported

and fueled by the now famous 1972 Chouinard catalogue, this group of climbers

adopted the strictest (cleanest) of “clean climbing” philosophies:

no bolts, no pitons, no aid climbing. If a route couldn’t be climbed

free with nuts, it was to be left to the birds and the chipmunks.

Also, a strict no publicity maxim was enforced: no guidebooks, no magazine

articles; one was even to be careful talking about the climbs. For the most

part, these climbers believed they were here to respectfully share this scared

ground with the spirits of the earth, and this sense of respect included

a strong conviction that broader visitation by outside climbers would only

foul the nest. Although these ethics may now seem a bit extreme and counterproductive,

one could consider they sprung from at least three rational concepts: “territorial

imperative”–the local climbers grew up with this as their backyard; “ecological

logic”– fewer climbers equals less environmental impact; and

(to quote Chuck Pratt’s advice), “keep your mouth shut” when

you ‘find’ a

new climbing area – what really is to be gained when you tell everybody?

And so the 70s unfolded as a period of daring climbs, few climbers

and many adventures. Numerous first ascents were not recorded. Paul Gleason,

a protégée of John Gill and a mentor for John Long, was most

likely at his bouldering and free soloing apex when he climbed around Omak.

But he kept quiet about his bold ascents. Other members of this group also

ventured up onto unknown territory.

Of the many brave outings during that era, one remarkable ascent, the west

face of the Lake Wall (AKA Eagle Cliff) deserves mentioning. Jim and John

Goss, with a handful of homemade nuts and a single rope, headed up this muti-pitch

route to overcome difficulty and danger with courage and skill instead of

technology and tools. This exploration stands as a signature climb of an

adventurous spirit that would all but disappear as an approach to the climbing

of these rocks.

The 1980s brought at least two new teams to the Omak area: Mitch Merriman/Herman

Harrison and Bruce Tracy/Phil Gleason. As young climbers, Mitch and Herm

were active in the Omak area as well as elsewhere in Washington. Mitch in

particular (often with other novice climbers) started his climbing career

in the Okanogan County. As often happens with beginner rock climbers who

learn climbing through their own discovery, Mitch had many close calls and

exciting

adventures.

Mitch contributed the following in a recent e-mail:

I started climbing in the Omak crags in the summer of 1982, mostly top

roping and rappelling shenanigans such as befitted my lack of training. I

knew how

to tie a water knot, figure eight knot and a double fisherman’s knot

and I knew how to hip belay and rappel with a carabineer brake (4-oval carabineers)

and whatever else I could glean from the pages of Mountaineering: Freedom

of the Hills. My gear consisted of an 11mm x 45m rope, two locking

Carabineers, four oval carabineers, 12 feet of 1” tubular [webbing]

that I tied leg loops in and wrapped the rest around my waist for a harness,

and 30 feet of 1” tubular for rigging anchors (slinging boulders, Ponderosa

Pine trees, mock orange, serviceberry shrubs or equalizing sagebrush bushes).

My shoes were leather hi-top converse basketball shoes that I would periodically

sew the soles back onto with dental floss. I and whoever I could trick/coerce

into it would top rope mostly on what I believe is now called “The

Practice Wall.” They were fifteen foot routes from 5.2 to 5.9. I took

an unroped fall while soloing in a 5.2 chimney…the first time of many

in which I really should have died.

|

|

|

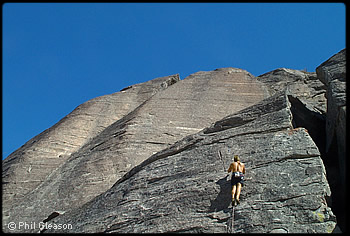

Omak Rock. © Phil Gleason. |

|

|

Mitch goes on to relay a horrowing tale of a top-rope gone bad, where he

set out to climb a mossy chimney with an anchor that had been set for rappelling

practice, about 25 feet horizontally out of line with the climb, and he persisted

in climbing this mossy chimney after a thundercloud burst its buttons. “The

higher I got the more the heavy wet rope began to tug me out of the chimney.

I began to feel desperate and called for slack and continued” …. “after

free falling for 20 feet, the slack came out of the rope. My belayer, 75

feet below with a hip belay, had been freaking as badly as I. He had wrapped

the rope multiple times around his body and been backing down the slope.

When I hit the end of the rope after 20 feet of accelerating free fall he

went airborne up the slope for another 20 feet. Neither of us got a scratch.”

Mitch survived the incident and added many fine climbs in the area, generally

in the moderate to 5.9+ range. He and a variety of partners were quite active.

Mitch and Michael Patterson climbed “Danison’s Delight,” in

1984. Mitch and Herman Harrison climbed “Linear Perversions,” aka “Spill

the Wine” on Omak Lake Wall in 1986. Mitch and Tom Bosden climbed a

five-pitch route, “Mitch and Tom’s Excellent Rock Climb” (5.8)

on the Mission Wall in 1989, and with Tom Bowden he climbed another five

pitch line on Eagle Cliff (5.9+) also in 1989.

Editor’s note: readers who climbed in the early ’80s may

recall this as the scariest rating ever before or since given in American

climbing. 5.9+ was reserved for routes that were of un-quantified difficulty,

obviously hard and at or near the top end of what any local climber could

do at the time. There was an ideological aversion to extending the difficulty

scale beyond 5.9 because it was originally conceived of as a decimal system,

and 5.9 had been defined as the hardest possible climb that could be done

without aid. 5.10 didn’t make sense; after 5.9 came Class 6, which

was aid. The rating “5.9+” often went without update because

many of these 5.9+ climbs were obscure or exceedingly run out in addition

to being just plain hard; many popular routes in this range eventually were

re-rated at 5.10 or 5.11.

|

|

| Background |

| |

|

| About Phil Gleason |

|

Phil Gleason has been climbing for forty five years,

and climbing in the Omak area since 1981. He pioneered many rock climbs

in North Central Washington, and has always been an avid photographer;

like many of us, he has taken to producing digital images in more recent

years. Several adorn this issue of the Northwest Mountaineering Journal,

mostly on reservation rock which is currently closed to climbing. He’s

been called Sergeant Rock since early 80’s because he was always

eager to go climbing, sometimes a little early in the morning.

|

|

| Kurt Danison |

|

Kurt Danison has climbed in and around the Omak area

for twenty five years, first exploring crags such as the “Mission

Wall” in about 1975. For the last ten years, he’s been more

active in exploring the wild rivers of the Intermountain West. Currently,

his telephone machine says he’s off on “the river of no return.”

We hope not.

|

|

| Herm Harrison |

|

Herm Harrison climbed around Omak in the middle

1980s. He still climbs, and was last reported in the Eastern Sierra

about

a year ago. He maintains a fine website that he calls “wormspew.” Check

it out.

|

|

| Mitch Merriman |

|

Mitch Merriman was most active in the Omak area from

about 1980 to 1986. Mitch describes a fond memory for the adventurous

nature of traditional climbing on uncharted rock. When questioned in

connection with this article, he said: “watch out for rattlesnakes!”

|

|

| Rob Jeter |

|

Rob grew up in the Omak valley and was extremely active

in the '70's and '80's; he currently works for the United States National

Forest Service, based out of Randle, Washington, and does accounting

for timber sales on the Gifford Pinchot National Forest.

|

| |

|

|