| Mission | Submission Guidelines | Editorial Team |

| Issue 1 | Archive |

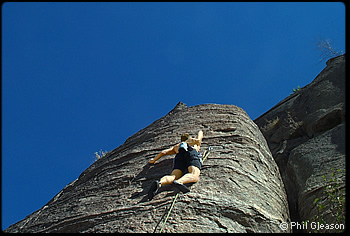

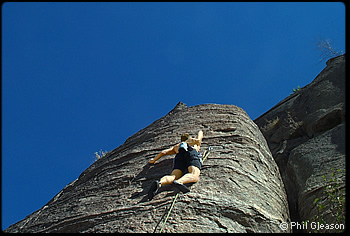

| Omak Rock Climbing | ||

| Part 2, By Phil Gleason |

|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

Like Mitch, we also had some “close calls” including one particularly close one with a car-sized loose block, wild bee hives encountered mid pitch, near misses with rattlesnakes, extreme heat, and run out 5.8 moves on loose rock. We adopted and supported many of the ethical values of the local group, and we generally made all our climbs from the ground up, using only nuts and camming devices for protection though we did take pitons and a hammer on our climb of Lake Wall, and even placed what are the first known bolts in the Omak area on that ascent. We also agreed that there was little to be gained from publishing anything about our climbs. When Bruce left the sport for ultralight flying and paragliders, I continued to climb with a number of the locals (namely Jim Goss, Rob Jetters, and Kurt Danison) and a variety of new climbers who began to appear on the scene. The routine lack of documentation and fixed anchors insured that several parties would believe they were enjoying a first ascent. For example, Mitch Merriman notes that his Eagle Cliff route reported above may have seen a prior ascent by the Goss brothers, but he and Tom Bowden found no trace of a prior ascent when they made their climb. This experience was repeated many times on Omak rock. Although Bruce and I had indeed placed a few bolts on our climb of Lake Wall in 1988, the real proliferation of bolted face climbing around Omak was to come with the arrival of a new face, Rick Hanks in the late ’80s. For good or bad, Rick was to have more influence on rock climbing in the Omak area than anyone before or since. Rick started climbing in the late ’80s, and received much of his direction and inspiration from the climbing magazines of that time. Because sport climbing was the rage, Rick’s orientation to rock climbing was the rap-bolted, sport climb. When he looked out across the hills above Omak, he saw an un-touched new frontier with endless possibilities. Like many traditional climbers before him, Rick thought of the guidebook as the culminating expression of the cragsman’s art and effort. Such ideas would soon lead him into direct conflict with the old guard. He and I made a number of climbs together, and as our friendship unfolded we had spirited conversations about the future of rock climbing in general and the Omak Rocks in particular. Rick was a believer in the bolted route and the publication of the area to insure advancement; I argued that the true value of the area would best be preserved if it retained it’s almost wilderness status. Although we had differing views, we both loved climbing sincerely and did not let our different opinions prevent us from going out and having a good time on the rocks together. And while I clung to my arguments, I did not feel it was my place to tell him how to climb or control him. Rick began his exploits with his brother Tom. They went up onto the old haunts and began bolting routes that had been “merely” top-roped before. Rick indeed found many beautiful lines, top-roped them, and then put in bolts that “opened-up” stellar climbs that proved to be great fun for other climbers to do. Unfortunately, however, his lack of experience made for some poor bolt placement on a few of the climbs. Rick’s unrestrained and relentless search for climbing and bolting new lines at first irritated and then infuriated the remaining locals. Even though many from the original 70’s group had moved out of the county, or had quit climbing completely, the few remaining old guard held a strong opinion and affection for the Omak Rocks. This fundamental conflict of bolting ethics was to come to a fateful confrontation one day when Jim Goss, accompanied by two Native Americans, took it upon himself to remove Rick’s sport climbs. Rick happened to be up among the crags that day, and on returning to his car found Jim hanging from a rope, eradicating the offending hardware. This story becomes more complicated when one pauses for a moment and asks: to whom does the rock belong to in the first place? As the history of land ownership would have it, the rocks above Omak fall under one of three legal jurisdictions: Indian tribal reservation land, deeded tribal trust lands, and privately owned land. The rock that formed the field for the escalating bolt war was indeed deeded land. And Rick had obtained permission from the “land owner” to bolt the rocks. After a brief and bitter verbal exchange, Rick went and got a sheriff deputy who promptly charged Jim and the natives with trespassing and destruction of private property. For the Native Americans this was a fateful slap in the face. They were on what had been their grandfather’s land. To be thrown off the land and charged with trespassing when they felt they were protecting the natural beauty of the area, was an insult that fomented enormous negative feelings. This incident had profound effect on rock climbing on the reservation for two reasons: (1) one of the Native Americans thrown off his grandfather’s land controlled access to the Lake Wall; and (2) this confrontation caused publicity and brought the question of rock climbing access on the reservation before the tribal council. Before now the question of whether climbing on tribal lands was permissible had not been asked. Prior to the bolt war this had not been a problem. Only rarely, if ever, did climbers see someone else when they were out climbing. Now the question received unwanted attention, and the climbers and tribal members were forced to confront the issue. Not long after this incident, Rick and I were invited to make a presentation on rock climbing, and a formal request for permission to climb on the reservation, before the Colville Tribal Council, in 1992, as best I recall. When we first got to the council chambers in Nespealem, we were met by a tribal businessman who was very enthusiastic about opening the reservation to rock climbers. As he saw it, climbing was a source of new tribal revenue from charging “Seattle climbers” with parking and day-use fees. “All we need to do is advertise.” I was uneasy, even queasy about this. Before the Council, we gave what we felt was a sensitive presentation with emphases on respecting the natives’ land. However, one by one, voices predominately negative to climbing the local crags were heard from the Council members. It was soon obvious to us that a strong majority opposed further white man use of tribal lands. As one Council member put it: “Here the white man comes again; this time they want to take our rocks.” The impression at the end of the council meeting was that rock climbing on the cliffs and canyons of the Colville Reservation was unwelcome. (Ironically, not only had the precipitating incident taken place on deeded trust land, not subject to Council control, but most of the developed (bolted) climbs were on deeded trust land on which the owner had given his permission for bolted climbing.) Sport and traditional rock climbing continue to make significant progress and development, largely in the permissible areas, and another very active climber came on the scene not long after the famous Tribal Council meeting: visiting geologist/climber Dave Jones. Dave already had quite an impressive climbing résumé when he briefly relocated to the Okanogan County. He brought a strong combination of talent and motivation. Like Rick Hanks a few years earlier, he too saw a huge potential for bolt-protected routes when his eyes caressed the gneiss outcrops that can be seen shining above Omak. Behind his Bosch were years of experience in establishing routes and talent for establishing exceptional climbs. In the few years he was active climbing in the Okanogan, he left a number of beautiful and challenging routes, the two most impressive were “Gravitons on Vacation” and the almost unbelievable “Omak Crack” on the White Block, high above the town of Omak. Dave left the Omak Valley in about 1994, and Rick retired from active route development at about the same time. For the remaining active locals, the sport routes that Dave Jones and Rick Hanks had established, plus the original and yet to be done traditional climbs made for enough climbing in this area whose access was always under serious threat. Yet new development came soon, in the form of bolt protected sport routes. This new activity was influenced by Rick, who built Omak’s first indoor climbing gym (at a local 3rd – 5th grade elementary school) and started climbing classes. Amazingly this climbing wall may have been the first built in a school in Washington. A nagging elbow injury caused Rick to retire from active climbing. He turned over the indoor climbing program to Sean Kato, a young teacher who had began climbing while attending college. Sean was inspired by Rick’s passion and enthusiasm for climbing, and the way he encouraged and coached the students. Sean: “Rick’s passion for climbing has allowed and will continue to allow many students and adults from the community to experience climbing in a safe environment.” In the spring of 1996, after the access problems seemed to have cooled down, Sean, with Mike Wyant (an experienced and active mountaineer who had been climbing for years around Omak) began establishing new routes in the Omak Rocks. Climbing with other locals Greg Hamilton, Zeb Groff and Anthony Mannino, Sean was instrumental in adding over 60 climbs, the majority in the 5.8 to 5.11 range. New routes continued to go up until access problems once again resurfaced in the summer of 2003. To quote Sean from an email: A new landowner below the Reservation Rock face enacted a climbing closure on the Res Rock. I tried to get the word out to people that climbed in the area about the closure. A couple of weeks after the closure a group of climbers, not knowing of the closure, were out climbing on the Res Rock. This same day multiple groups of people were out climbing on the Hideout Rocks, the Practice Wall and various crags above. The new landowner was also out and saw the many climbers. He yelled at the climbers on the Res Rock face to leave but they kept climbing. I had been at the uppermost crags all day, working on new routes, and was unaware of what was happening below until I returned to my truck at the end of the day. The landowner had become so upset that he left a lengthy letter on my truck stating that the Hideout Rocks, Pine Street Station, the Weeping Wall, the Practice Wall, and the parking area were all shut down. He said that anyone trespassing or parking on the land would have the tribal police called and cars would be towed.

As Sean reported above, the access to The Hideout and Reservation Rock was dealt an apparently fatal blow when the land changed ownership. The present owner, a friend of one of the Native Americans thrown off the land during the bolt war, is building a house and wants no climbers whatsoever on his land. The hope for future climbing rests with the positive relationships Sean has established with private owners. Certainly much other rock on the reservation is not so carefully guarded. But climbers who venture there carry the burden of trespassing on Native American land or stirring up related concerns. Keep in mind that, should you enter tribal land, you may be confronted by those who feel violated by your presence and your activities. Such is the access situation on the Omak Rocks as of spring 2004. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Continued <<Prev | 1 | 2 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ©2004 Northwest Mountaineering Journal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Site design by Steve Firebaugh |