|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

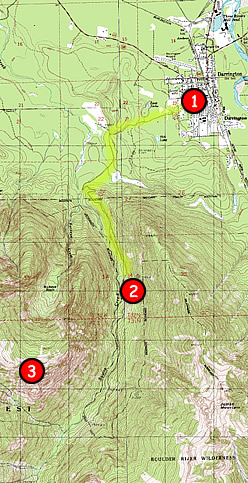

Happy hour is underway at the Balcony Bivy, eleven pitches up. Above us, three ropes are draped across the dappled distance and on the ledge much of our gear is arranged in little piles anywhere that is flat. The stove roars against the tranquility as we discuss freeze-dried options and locate our spoons. Bill’s bourbon makes yet another round and I am content to sit with friends and watch as the stars come into focus across the night. Soon the smell of stroganoff lures the resident rodent out of his cedar bush and into the danger zone. We are just guests however, so we make an offering of nuts and berries closer to his territory and the diminutive rat retreats. For four years I’ve felt like a maddened pit bull, slobber flying and flinging itself against a glass door, over and over again. My whole life had begun to ache with the hollow thuds of pounding my forehead on sun-burnt stone. Eventually we were packed, our dinners finished, the bourbon just a memory. Patience is a virtue they say and the next morning I am awakened by the resonant rustling of a bivy sack. Miles above me the skyline glows red as our fin of granite crashes headlong into the solar wind. Miles below me the music of the trees and the creeks harmonizes with the muted colors of the almost dawn. We are assembling ourselves to the sound of boiling water and spoons in coffee cups. The clicking of carabiners joins the soundtrack as a golden tide floods the wall and the deep shadows of night are flushed away by the clear light of the Darrington day. Another hour and we are jugging; a pitch apart, each of us, pulling on the handles ’til our elbows swell. Four hundred feet of Stairmaster and then we start leading again. Whatever demons got conjured by the night or obsessed upon at home, once up on the new pitches I was past them. Like caressing clouds or riding silk, the textures responded to the gentlest of discoveries, the barest of depressions made all the difference. The fifteenth pitch was the golden one; the one up out of “The Feature,” the one up into the open blankness. Knight moves, up and right. Finally, one foggy morning came the ripples, the connectivity, the sequences, feet shuffling, balancing, runouts and hammering. It had been there all along, waiting for us to figure out how. It’s intimidating sometimes, when confronted with a lead put up the previous week in a seizure of grinning optimism. But then the next week comes along, fixing more lines and hauling water. Moving up the wall, everything goes smoothly when the time comes. All the pitches below become so well rehearsed. We’ve made a summer’s project of rehearsing each movement, practicing the rhythm, cadence and signals of each pitch. A sort of romantic fog enshrouds the most rehearsed of the pitches. Thumb on the crystal, palm in the dish and right toe behind the little flake. Up to a palm slapper, rock onto the toe, hard to believe but the same motion seems to work every time. Green voodoo Thirty something years since I came looking up these valleys, came looking for a fable I’d heard across a campfire somewhere. We’d found the local hardware store open that sunny morning so long ago and behind the counter was a stovepipe-skinny and buttless old codger in bleached-blue overalls. He listened with patient good humor as we explained our quest and allowed that nothing he could think of would get him up on those walls but that they were indeed nearby. Truly big hunks of granite were living among the primal forests of western Washington! Some eighty-odd miles northwest of Seattle and perhaps a bit more than twice that far from Vancouver, in a forgotten corner of Washington’s Cascades, lies a mysterious mountain valley, not all that well known in the world of climbers. Immediately south of town, two parallel creeks flow out of the wilderness and there along the upper reaches of Clear Creek and Squire Creek is where the great gifts are. So we went rubbernecking that day, way back when, grinning and bouncing up the logging roads in search of big thrills. As it turned out, there would be enough for a lifetime. Up among the cedars, just like the old guy said, were the “ledges,” amazing domes of granite rising for one and two thousand feet from forests of 200-foot hemlocks and giant cedars. Squire Creek Wall was plainly visible from the front seat of an automobile in those olden days. The road ended in a clear cut. We gaped at it without making any attempt to get out of the car. Whatever that thing was, it was way outta our league. Huge for sure, but for a couple of kids with EB’s and a rack of hexes it looked like the dark side of the moon. Towering over twenty-five hundred feet above the valley and over a mile wide, the complicated east facing rampart remains a little known enigma to this day. Even though we made attempts in a few places, we just never discovered the right mindset for Squire Creek Wall. Twenty-five years would pass before I got brave enough to wade on over and try climbing again. Back on that first day in D-Town, so long ago, we didn’t linger very long… Big fuggin’ rock for sure, but we were already turning around. The wisdom from the Ace Hardware man was that Clear Creek had other big stones and so we shimmied back outta the sticks and made the correct sequence of turns up into the adjacent watershed. The road climbed through the forested hillside with expectant switchbacks and we marveled at the deep green camouflaged light that flooded the forest floor in glowing strokes of emerald and ochre. Our first glimpse was just a flicker through the forest, the Witch Doctor leaping high above the hemlocks. Voodoo can be so subtle it would appear. It’s not like I ever felt the push of the pins or the anything like that, we just slewed on blithely up the gravel track and marveled at the sights. Boulder strewn creeks gushed with spring’s ardent runoff and the smell of the forest filtered into the car. And then we gotta load of the other side of Exfoliation Dome. The west face was incandescent in the afternoon light, floating a hot thousand feet above the trees, its iconic saddle-shape so indelibly Darrington. The voodoo musta been pretty smoking’ stuff for we had gone from “how do you do?” to love-at-first-sight in the space of half an hour. Luminous stripes of rounded stone rising into thin air. A year later on the 23rd Psalm, Greyell and I had got stapled in for our first bivy in the Darrington area. It was our first bivy anywhere actually. Chris had a sloping ledge and I had half as much and a hammock. The next day we faced several more aid pitches and then a buncha easy free climbing. Some hokey nailing in corner seams and Chris got a sling belay on a bomber flake. Then after a few minutes of gentle jugging it was my turn. A brief but decent crack arced out left and then went zippo thirty feet short of anywhere. Thirty feet of smooth rock that would so amazingly lead me to a day in the future where I would still be waking up on small ledges, still suspended somewhere between sunlight and shadow. Thirty years ago. An old idea slipping On a day in late 2004, as a last stand against the marauding months of soggy grey, a few of us came looking for something to see us through. Laughing and yarning from the safety of the rainy trail, we marched across the giant muddy wounds of the landslide and yahoo’d our way up the remains of the old road. These days the trees along that road cut are much taller than they were back in the day, and it is entirely possible to walk along absorbed in camaraderie and good cheer and nearly miss the whole damn thing. Only a thin screen of young alders and cottonwoods attempt to mask the gravity of it all, and on that day Hanna and I had lingered longingly, looking, ducking and maneuvering for an unobstructed view. There it loomed, so grey and dripping, in its horror huge and gripping,

Somewhere in time the old witch doctor musta twisted the needles back and forth and somewhere in my brain, long forgotten pathways glowed as brightly as ever. Across a half a lifetime I was being shown another opportunity. Once again I walked through the valley, in the shadows of the ancient cedars; and gaped. A few long winter months later I was back, early enough in the spring that the ferns hadn’t sprouted or the underbrush yet grown hooks. We just wandered up the road, and listened for the creek; when the road seemed as close as it was gonna get, we dove off into the big green and to our surprise arrived at a large gravel bar alongside the creek in a scant few minutes. The crossing was sunny, knee deep and directly beneath the wall. On the far side of the torrent we sat on rounded river stones and changed back into our hiking boots. Raising our heads and looking above, we finally got our first unobstructed view. So we spent the next three seasons thrashing, several different friends and I, and got ourselves a dozen pitches up after maybe twenty-something days spent working at it. At times the progress was so paltry for the effort expended that completing the route seemed a hopeless fantasy. The higher we got, the harder it was to get any work done. At one point, grasping at straws really, we ’shwacked up the ridge and had a look over the edge. Getting that look took two brutal days, and frankly, the view was appalling. I rapped over the side in a few places and took pictures but the finish didn’t look particularly friendly. Dan and I burned another beautiful weekend attempting to walk around the wall from the other side. When a full day’s steep jungle thrash failed to get us anywhere close we were thoroughly convinced of what we’d known all along. In the end it was neither politics, nor morals, nor fear of the wilderness police, but simple expediency that kept us on track. The ethically and physically easier answer was to just go up there and pound away on the lead with a hand drills instead of trying to get to the top and rap down the thing. At the same time Dan and I had discovered The Cookie Sheet down in Yosemite. Springtime putting up new routes in the California sunshine had us all dialed in by the time the snow melted out of Squire Creek. What happened in the Valley was that I finally learned how to drill 3/8-inch bolts on the lead as quickly as I had been able to do quarter-inchers back in the day. We’re talking hand drills here, same shtick since the time of Tut. Hammer hammer, twist twist. |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Continued 1 | 2 | 3 | Next>> |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ©2009 Northwest Mountaineering Journal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Site design by Steve Firebaugh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||