|

|

|||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

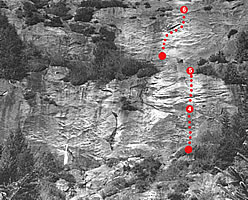

Too hot to think Eventually the big dark turned to springtime and the fresh sun found me paired with Bill Enger and a new sense of direction. We knew that we could climb the remaining rock and we also knew that to try and make progress with even a two-day window was pointless. Accomplishing anything further without a major time investment was impossible. We took to staying on the wall for three and four days, sleeping on the ledge and pushing the route upward as much as we were able. The Balcony Bivy became our home away from home. We stashed waterproof river-rafting bags containing all our bivy gear, stove, fuel, hardware, tequila etc. All we really had to do the first day was to get ourselves, sufficient water and a few precious limes up to this eleventh pitch oasis. Around 3:00 p.m. the wall finally slips into shade and cools off enough to let us fix ropes for tomorrow. Until then, it’s just too hot to think. So we wait and we sweat, each of us glistening as we sit and simmer like poodles in a summer Pontiac. Scalding.You actually need to put a piece of foam down on the ledge before you can sit in shorts. This time is a gift, I remind myself, gazing broken-necked up the monstrous expanse above. The bargaining continues, two pitons, three TCU’s or still more hooks? How much water have we got? One more day? Two more days? Dan’s masterful twelfth pitch takes off from the ledge and above that shadowed corners tease us with a slender strip of shady solace. Then in a final burst of streaked radiance the fire is gone. Swiftly comes the shadow; finally comes the shade; we are offered respite from the sun at last. Our desire to climb recrystallizes from the stir-fry on the ledge and our lethargy retreats with the advance of the great shadow racing across the valley. The brightest of the day has passed. The slow and slippery hours under the microwave have been air conditioned with a big blue filter. At first just a sly grin of freedom, the shade is a subtle reminder to get up and keep the program rolling. We’ve been at it for about 10 hours at this point. Surely a few more can still be done.

The story is much too long to tell… or even to remember coherently. Four years of going back again and again. The early morning departures, hiking up the old road, chilling creek crossings under bluebird skies, up through the beautiful old forest and then out into the sunshine and the heat. El Projecto Profundo.

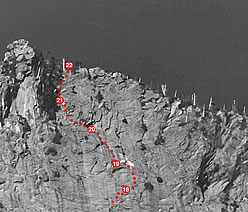

Deluge In July I went out there with Greyell for a three-day adventure. He’d known all along that we were tapping away year by year and was eager for a taste. The Balcony was stocked with gear and water and the frontlines were the top of the fifteenth. In hindsight it seems so nostalgically amiable, to be working 16 pitches up and not 20-something. Chris had come out to “donate” a pitch and also I think he realized we needed all the muscle we could get. So I floated and prayed my way up the fifteenth then got myself buckled in for the show. I know only a handful of people that I can drag fifteen pitches up a wall and then point with glee up into the blankness — a fairly perverse talent to be sure. So we guzzled gator-aid and red bull in the sunshine while I cheerfully loaded Chris up with hammers, wrenches, pins, hooks, cams and widgets and then got my camera ready. Now Chris is about as naturally optimistic as they come and to be honest, the pitch looked like it offered enough to work with. So without any drama at all he balanced up under the little arch, kicked me in the head and was on his way. Two new pitches we got before glad-rapping and basking in the sun. Leaving our lines fixed above us, we were proudly sharing happy hour at the Balcony when great thunder heads started rolling across the horizon. Oh, but such weather is classic Greyell! They don’t call him the Rainman for nothing! Soon a pitter-patter of heavenly spray forced us into our bivy sacks and as we hunkered in the clammy goretex, we realized we were stuck here without first jugging at least two pitches and collecting our ropes. Two hundred feet to the side of us a block the size of a dishwasher rolls out of a chimney and sprays supersonic shrapnel across the face below.The rain let up for a bit around seven o’clock and Chris exploded from his bivy sack with the announcement that he was gonna jug up and recover enough rope to rappel. Meanwhile I packed like a wild man, and by the time he returned, I’d gotten all the gear mashed into the dry bags, and was anxiously looking at the thickening bank of billowy black. My lead rope was still hanging from anchors at the top of pitch fourteen! We decided to simul-rap in view of the late hour and made the snowfield just as darkness was upon us. Moving into the trees with headlights we found our way down through the forest with minimal pain. After several days of ninety-degree temperatures Squire Creek was a raging monster in the darkness. The only light in the creek bottom was provided by fantastic electrical explosions followed by immediate and thunderous applause. The cobblestone beaches on either side had vanished beneath the swirling foam, and the roar of the creek drowned out everything except the chest pounding rumble of Thor’s hammer. Chris was shouting something about using a rope to belay the crossing. As we stood there in the darkness and the deluge, with lightning bolts illuminating the scene, I observed that I had never had to belay a creek before, but this sure seemed like a good place to start! Chris splashed around the edge of the torrent and found a belay behind some flooded trees and I moved downstream and out into the current… my little Petzl Tikka provided just enough light for me to stay oriented… raging ice-water surged up to my chest at one point and by the time I staggered from the flow on the far side the all-consuming chill had become alarming. The day had been in the 90’s, the air was muggy but warm, and as soon as I was out of the water, the chill vanished. I waded upstream to try and find a better position for Chris’s crossing. A giant bight of rope had been pulled out into the current and the great loop arced its way downstream so far that I thought Chris had lost his end. Much screaming confirmed that indeed he was still tied in. As I hauled on the slack, the rope cut back upstream and sprang from the water like a team of flying fish. Soon Chris plunged into the current and battled his way across to a great welcome from me. The rain assaulted us in heavy sheets, but at this point, we knew we were safe. The old road was just a hundred yards uphill, then a short mile and a half walk back to the car. It was one o’clock in the morning. Finality A week later Bill and I are fairly well into our second day on the Daddy. After jugging three pitches and leading five more, we have just reached the start of pitch twenty and it’s already getting late. We have only a few hours and the opening meters of the groove are steep and polished. It’s a shallow dihedral actually, with just a teasing barely-seam in the corner. Not even enough for a thin wedge of chrome. A squirrelly sequence up off the belay got me going and then I started to aid it, Warren Harding style with 1/4-inch bolts and bathooks, a few hollow-sounding pins and the odd micro cam. After a bit of aid the corner changes to something else and the old black magic is back. Let’s hear it for the voodoo dude. Twenty pitches up and I’m gonna step out of my little chicken-shit shoe-string aiders and do the old slap and smear. Ten feet to the knob? A black bump with a sorta stance. Where the fuck IS the last fat one anyway? Buckets and screamers for fifty dollars please! The daily double! My little piggies grip the sweetest of pegmatite knobs… No sir, not this time!… another ripple for the left foot and then what? Pound like a wildman! Don’t be looking around, don’t pay no ten-shun to your toes, do not look at the length of ropes trailing down. And above all do not stop hammering. There won’t be any comfortable way home tonight without transcendental hammeration. More hammering. Keep hammering, pound and twist, pound and twist. Three visits to do the damn pitch while Bill hunkers supportively in the gathering gloom. Seven days working the one pitch to make it 5.9 A2. And then Dan appeared from the past. Now Dan’s a California dude and learned his craft in the Yosemite of the seventies. His glorious Crest Jewel on North Dome has become a great Valley classic. That’s a whole ’nuther story, but perhaps there is some sort of serendipity in that ultimately he and I would get to know each other and wind up tapping on the Daddy’s door. Dan’s vision made the twelfth pitch happen and his tenacity again pushed the fourteenth up to where we could finally look up at our future. But Dan got married just as Bill and I got to be friends and the world carried on, big chunks of stone notwithstanding. Then late last year, as the leaves were already taking on an alarming hue, although maybe from dryness as much as from our advanced position on the calendar, we got what we knew would be our last opportunity. “Dan, my man, ya gotta come join us for the big event!” I’d said. After a whole season without getting up there we coaxed him off the bench by selling the prospect of actually pulling over the top. “Just jug with some water and freeze your ass for a few hours and we just might pull it off” we had teased. “Nobody wants to miss out on a furreal epic do they?”

All week long I’d kicked myself; if only I’d hammered a bit more the previous time and gotten it buttoned up. I mean, isn’t having numb feet for two hours OK? Now Bill and Dan crane their necks to watch. I sure as hell hope that the rest of the freakin’ pitch really is only 5.8 after all my fat talk from the safety of a rap station. Thirty more feet and damned if a killer cam placement ain’t in the middle of it. The top is close enough to smell. The skyline we’ve gazed at for years is close enough to see the lichen and tree bark! At 3:30 in the afternoon the little bell waits seductively 250 feet above us. Bill moves out on the next pitch and starts a bolt about 10 feet above the anchor. Halfway through the process the drill bit explodes and he decides to blow it off and lead out around the corner on a whim and a prayer. The ancient witch doctor must have been watching the whole thing because after having moved around a couple of blocks and small corners Bill found the crack. A narrow, right-facing corner pointed straight toward the sky, and the crack, oh yes, the crack was a perfectly clean one-inch fissure. Somewhere, just to add another layer, the voodoo man was surely chuckin’ the chicken bones, for Bill didn’t have anything that fit. The 5.9 corner ends at a great belay stance 50 feet above and so he just ran it out. The locks are great, the stone is clean and the summit near. That lead was great, but I’m glad for the beta; I’ll bring a couple of three-quarter camalots when the lead is mine. There was still more to come. The finest line lay out to the right but at this hour any drilling would have cost us the top. So we found a sleazy way off to the left that could be blustered through with a bit of gear and chromoly. The real finale would be out on open rock and then directly to the summit. In the meantime, Bill brought his Cascade moss-climbing skills to bear and gardened his way up some steep licheny blocks until an Amen tree stood up for the last belay slings. We were just a few more mossy meters from the still-shining crest. Finally, we top out into the sun at last. The stepped heather ledges are slippery in rock shoes but warm in the last golden rays of the day. Without much time for contemplation or reflection, finding a workable rappel point is our immediate concern. A solid silver snag that I’d seen on the skyline from below all these years turns out to be in just the right location for our needs. With only a quick look around, we hitch some bits of webbing around the old snag and tie our ropes together. The time is 6:30 p.m. and we begin our rappels just as Whitehorse stretches out and slyly steals the last sip of the sun. |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Continued <<Previous | 1 | 2 | 3 | Next>> |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| ©2009 Northwest Mountaineering Journal | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Site design by Steve Firebaugh | ||||||||||||||||||||||