|

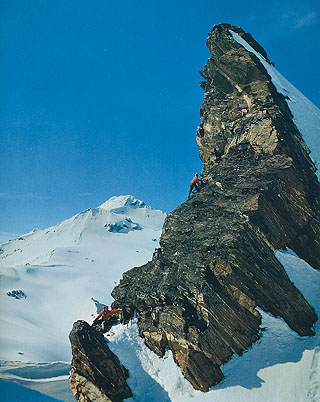

| David Nicholson (left) and Tom Janisch pause above the White Chuck Glacier, May 2007. (Map, 400kb) |

|

Pioneer climber Hermann Ulrichs described the North Cascades as two mountain systems superimposed on each other. One is the chain of volcanos extending from Mount Lassen in California to the Canadian border (which he called the Oregon System). The other is the more complex and granitic chain extending from north of Mount Rainier into the British Columbia Coast Range (which he called the Canadian System). Ulrichs wrote in 1937, "The commingling of these two diverse systems gives an inexhaustible variety to the range."

Nowhere is this variety more evident than in the Glacier Peak region. Visible from most high points in the North Cascades, Glacier Peak stands robed in ice, its outline soft in comparison to the craggy summits that surround it. Ulrichs probably had Glacier Peak in mind when he wrote about the Cascade volcanos: "Though actually the youngest of our mountains, the impression given by their tranquil repose and ample flowing contours is that of great antiquity. Other mountains seem young and turbulent in comparison." The snows of Glacier Peak were an early attraction to ski mountaineers. On July 4, 1935, Hans-Otto Giese and Don Fraser made an unsuccessful attempt to ski the peak from the north. Giese was one of the true pioneers of skiing in the Northwest, with ascents of Mounts Rainier, Adams, St. Helens and Baker starting in the late 1920s. Don Fraser was the winner of the first Silver Skis race on Mount Rainier in 1934. They were a remarkable pair. Three years after the attempt by Giese and Fraser, Dwight Watson and Sigurd Hall successfully skied Glacier Peak from the Milk Creek drainage. Dwight Watson was enchanted by the Glacier Peak region, which he called "The Charmed Land." On Memorial Day, 1937, he made a ski-climb of White Mountain with Sigurd Hall after traversing from Indian Pass on skis. He observed that "the White Chuck basin looked ideal for skiing." A year later, on foot, he traversed the mountains east of Glacier Peak now known as the Dakobed Range. Watson called these mountains "The Delectable Range," a reference perhaps to the appeal of the glaciers and snowfields for skiing. In May 1959, photographer Ira Spring organized ten Mountaineer friends and flew with pilot Bill Fairchild to the Honeycomb Glacier south of Glacier Peak. They spent six days skiing and photographing in the area, including a ski ascent of the volcano. Spring's photograph of two climbers scaling "Tiger Tower" on the Honeycomb-Suiattle divide was published in the 1969 Superior book, The North Cascades National Park. Their aircraft-assisted trip is a striking reminder of how wild the North Cascades were in the 1950s. The range was as remote as many areas in Alaska or Canada are today. Now that Wilderness designation has blocked aerial access, the North Cascades are more difficult to reach than many unprotected areas farther north.

In 2007, after I conceived the idea of skiing the Cascade Crest from Mount Baker to Mount Rainier, I noted a blank on my map between Glacier Peak and White Pass. My 1989 trip along the Suiattle High Route had ended at Glacier Peak after arriving from the north. I planned a trip in early spring of 2007 from White Pass south to Stevens Pass. This left a gap of only five miles between White Pass and my 1989 route across the Suiattle Glacier. Holding snow into summer, this was the logical choice to be the last segment of the Cascade Crest ski project--my "golden spike" (see map, 400kb). On Memorial Day, 2007, David Nicholson and I drove from Seattle to meet Tom Janisch of Wenatchee at the North Fork Sauk River road. About two months earlier, Paul Ekman and I had skied up this valley during the White Pass to Stevens Pass traverse. The difficulty of negotiating the Sauk in early spring put me in no hurry to return. By Memorial Day, I reasoned that the trail would be snow-free and the deep snows of White Pass would be consolidated. We parked at the Lost Creek bridge, where a road closure sign was posted. The closure added about 2-1/2 miles to the approach. David and I brought mountain bikes for the road, but Tom had lent out his bike for a few days, so he walked. The morning was cloudy, drizzly and cool after a night of rain. Typical Memorial Day weather. We hiked the North Fork Sauk River trail, encountering several blowdowns, but nothing that slowed us down too much. At Red Creek a log jam offered an easy crossing, but it deposited us below a precarious patch of dirt that led out of the stream channel. We made good use of our ice axes to claw our way up the duff.

From Mackinaw Shelter, we hiked to timberline and traversed the mostly snow-covered trail to White Pass. The clouds, which were supposed to clear in the afternoon, remained stubbornly in place. We navigated by compass and altimeter to the White Chuck Glacier. In mid-afternoon, the clouds finally broke and we had a glorious view of Glacier Peak above the mists. We camped at the northern lobe of the White Chuck Glacier on a windy rock ledge. On the second day, we left camp just as the sun arrived. We climbed frozen snow to the Suiattle Glacier divide and continued northward, climbing the Gerdine Glacier to the saddle next to Disappointment Peak. The final slope to the summit offered an outstanding view of the country we had traveled through. On top, I scanned the horizon from Mount Baker to Mount Rainier and tried to absorb the fact that I had finally completed my Cascade Crest ski project. All that remained was to return home safely. Around 10:30 a.m. we began our ski descent from the top. The initial southwest-facing slope was crusty, but on the more easterly-facing Cool and Gerdine Glaciers, we found excellent corn snow. We admired the marvelous open country south of Glacier Peak and agreed that we could happily spend many days skiing there. Unfortunately we had just two days of provisions with us, so we returned to our windy camp and packed up. We savored the views along the traverse to White Pass, country that had been hidden by fog the previous day. We were able to ski most of the traverse from White Pass to the trail switchbacks above Mackinaw Shelter. The sun was hot during our descent to the valley, very different from Monday's weather. Fortunately, the old forest provided comfortable temperatures on the hike out to the Sloan Creek campground. After David and I pedaled back to the cars, I drove my car back up the road past the closure sign and picked up Tom, saving him time and energy for his long drive home. We all agreed that it had been an outstanding trip. As the "golden spike," the final segment of my quest to ski from Mount Baker to Mount Rainier, our ascent of Glacier Peak was uniquely memorable for me. --Lowell Skoog

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Previous | Next | Overview - Skiing the Cascade Crest | The Alpenglow Gallery |