Part 3 - The Mush Season

The most frustrating time of the Cascade snow year may be the mush season.

There’s plenty of snow, but the quality takes a turn for the worse.

Mush Season Characteristics

- Based on my journals, the mush season typically occurs between about

the 2nd week of April and the 3rd week of May.

- The exact timing varies from year to year.

- This is the time when the snowpack makes the transition from winter

accumulation to spring melt.

- Typically we see an alternating sequence of cold/wet and warm/dry

weather systems.

- Just when you think the snow may be consolidating another cold storm

arrives, extending the mush season yet again.

- A one-foot dump of snow can easily take a week to consolidate.

- When the weather does turn nice, it sometimes gets too warm too fast

(The Big Warm-up).

- Melting penetrates deeper into the snowpack. Buried snow layers

that were strong earlier in the winter may break down.

- Overnight freezes may be weak due to longer days and warmer

temperatures.

|

|

|

Tom Janisch and Adam Vognild enjoy skiing without packs

on the Eliot Glacier during a ski orbit of Mt Hood, May 2006.

|

|

What Can You Do?

- As I mentioned earlier, the snow season typically advances from

south to north, so if it’s mushy in the North Cascades, try skiing

farther south where it may be more consolidated. You might ski around Mt

Hood (where the picture above was taken), Mt Adams, St Helens, or maybe

the Goat Rocks.

- Or go east, for example to the Chiwaukum Mountains, near Stevens

Pass (photo below). I haven’t done much skiing in the Chelan or

Pasayten Mountains, but I imagine this might be a good time for those

areas too.

|

|

|

Carl Skoog ascends Snowgrass Mountain in the Chiwaukum Range

with Cape Horn in the background, May 1988.

|

|

- This can also be a reasonable time for lower sections of the Cascade

Crest between Glacier Peak and Snoqualmie Pass. In 2007 we skied from

White Pass (near Glacier Peak, shown below) to Stevens Pass in early

April, trying to catch reasonably consolidated snow before it got too

thin.

|

|

|

Paul Ekman traverses toward White Pass with Indian Head Peak

in the distance, April 2007.

|

|

- It’s common to have pretty dramatic warm-ups in spring. You

need to be especially wary of the first big one.

- Freezing levels may spike thousands of feet higher than

they’ve been most of the winter—9K, 10K feet or higher.

- This can be especially bad if it follows a lot of cool/wet weather

with snowfall.

- Admit it: When you’ve been day-dreaming all year about a big

trip, it’s hard to let beautiful weather slip by.

- But I’ve learned to try to resist this temptation. (Or at

least head south or east or somewhere that may be more consolidated.)

It’s best to let the first big warm-up pass and do its

job—stabilization.

- Fair weather rarely lasts long in the Cascades, so if you’re

planning a long trip, you’ll probably have sit out a spell of bad

weather before you get another shot at it.

- You’ll have to wait for the next good weather window and hope

that there isn’t too much new snow in the meantime (or that spring

slips away before another spell of good weather arrives).

May 2008 Warm-up

- The spring of 2008 had some classic warm-ups. The first one

happened in mid-May after a long spell of cool/wet weather.

- Shown below are excerpts from the Northwest Weather and Avalanche

Center (NWAC) forecast from May 14:

- Key phrases include: “A major change in the weather

pattern” ... “Freezing levels near or above 15,000

feet” ... “widespread spring avalanche cycle”

- Shown below is Kitling Creek basin near the North Cascades Highway,

the day after the NWAC warning was issued.

- The upper-left photo was taken in the morning, before

the day warmed up.

- The lower-left photo was taken in the afternoon, after

some major slides occurred.

|

|

|

Kitling Creek basin on May 15, 2008.

The yellow oval shows the avalanche starting zone.

A falling cornice triggered the slide.

The red 'X' (lower-left photo) marks a slope that

remained safe throughout the day.

Photos © John Morrow and Larry Robinson.

|

|

- The yellow oval shows the avalanche starting zone, high on

the NE shoulder of Kitling Peak.

- Telephoto views indicated that the slide was triggered by a falling

cornice.

- The red X in the lower-left photo marks a slope that did not

avalanche. Slopes like this one—north facing, lower angle, not

subject to cornice falls or shedding cliffs—remained safe

throughout the day.

- The party that took these photos stayed on safe slopes during the

day, got to watch the avalanche show, and had no problems.

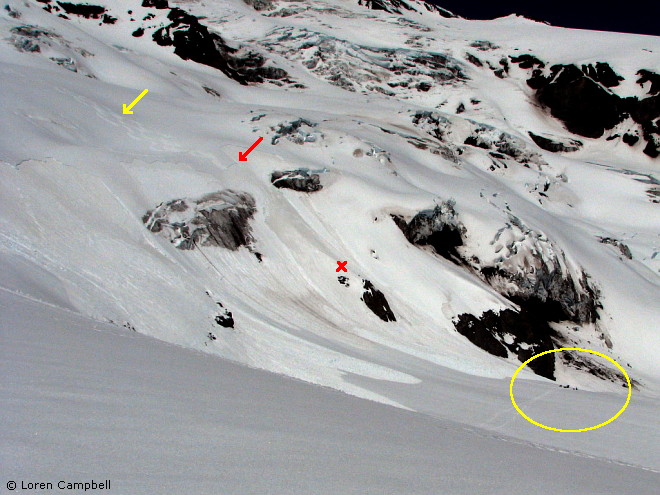

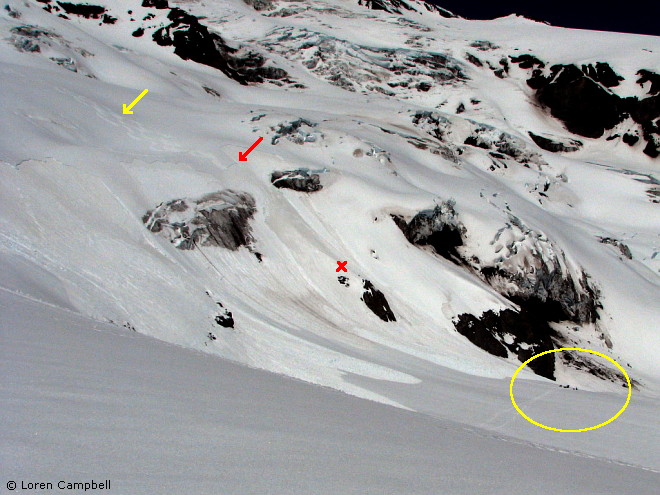

June 2008 Warm-up

- In many years, one big warm-up would be it for the spring, but 2008

was different. Shown below is a special warning issued by Northwest

Avalanche Center (NWAC) on Tuesday, June 10, after they had stopped

normal operations for the season. The warning was issued one day after a

killer storm hit Mt Rainier.

- Key phrases include: “Paradise has received about 30 inches of

new snow!” ... “accompanied by very strong winds” ...

and they predicted: “freezing levels reaching 9 to 11,000

feet” ... “Wet loose and possibly wet slab avalanches”

... "some slides entraining significant snow"

- Below is a picture of Mt Rainier taken on Saturday, June 14. It

shows skier-triggered slabs above the Nisqually Glacier.

- The yellow arrow points to the ski tracks. The red arrow marks one

of several avalanche crowns. The red X shows the location of a

snowboarder who was swept down the slope by the avalanche but not

seriously injured. A party of climbers who helped him afterward is

circled by the yellow oval.

|

|

|

Nisqually Glacier on Mt Rainier, June 14, 2008.

Yellow arrow shows the tracks of skiers who triggered a slab

avalanche but were not caught.

Red arrow marks an avalanche crown.

Red 'X' shows where a snowboarder climbing the slope was

caught by the avalanche.

Yellow oval shows a party of climbers helping the

uninjured snowboarder.

Photo © Loren Campbell.

|

|

- In my experience, mid-June slab avalanches are pretty rare in the

Cascades. But if they’re going to happen, these seem like the

perfect conditions for it, so they’re worth remembering.

- It’s also worth noting that these avalanches occurred two days

after NWAC had replaced its special warning with a generic spring

avalanche statement. This points out the need to stay on your toes in

spring, especially when NWAC has stopped normal operation.

Summary of Mush Season Hazards

- Most often the hazard involves sloughing during the heat of the day.

- Slab avalanches are rarer, but still possible.

- Being swept over or into terrain hazards is normally a greater

concern than being buried. I think this is because the snow is so

dense—you tend to pop to the surface.

- You need to stay aware of how well the snow froze overnight, how

quickly it is warming during the day, which slopes are warming the most,

and whether they’re steep enough for slides to run.

- Beware of cornices and rock faces unloading.

Mush Season Tactics

- Time your movements to navigate south slopes early, before they

soften too much.

- If you’re going to travel in the afternoon, try to be on north

facing slopes.

- Be especially wary of rock faces and cornices. Most natural slides

during the mush season start here.

- Don’t ski above your buddies.

- If you need to descend a questionable slope, ski back and forth near

the top to slough it. This can be very effective at scouring the soft

surface snow down to a firmer layer. Then ski down the slide path.

- Don’t ski above your buddies.

- When you need to climb straight up a mushy slope, it may be best to

remove your skis and kick steps up at a slight angle (so you’re not

directly above your partners). Switching back and forth on skins is like

ski-cutting. If you switch back and forth, you might knock sloughs onto

your friends below you.

Employing Mush Season Tactics

- The most serious trip where I found myself needing to use these

tactics was in the Picket Range in 1985, during the 3rd week of May.

- The opening photos on this page (above) show recent and poorly

consolidated snow at the start of our trip. It was also warmer than

we’d hoped.

|

|

|

Jens Kieler descends into the Luna Cirque, Northern Picket Range,

May 1985.

|

|

- In the Luna and McMillan Cirques, we used all of these tactics to

avoid problems:

- Traveling from north to south, we camped high on the north side of

each NE-facing cirque so we could ski down the south facing slopes in the

morning and up the north facing slopes in the afternoon.

- We descended directly to the bottom of each cirque to avoid

traversing beneath the cliffs and icefalls.

- We ski-cut the slopes to sluff them and descended one at a time.

- Basically, we made the best of some not-very-good conditions. But

we had no scary incidents, and we learned a lot in the process. Today I

would probably let that warm spell pass and hope for less mushy

conditions later.

<<Prev

|

Intro

|

Timing

|

Winter

|

Mush

|

Gliding

|

Weather

|

Glaciers

|

Next>>

|