|

ntil July 2007, the Olympic Mountains were to me a mysterious cluster of glaciated peaks and glacier

lilies I had seen in my parents’ photo books. My dad and mom had not only explored nearly every peak and

valley in this mountain range, they had met while hiking in the Olympic Mountains and our family adventures

usually took us into yet-to-be-explored territory.

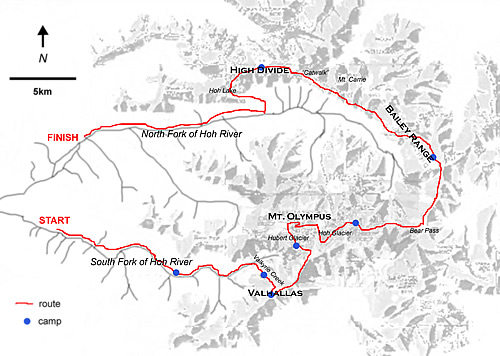

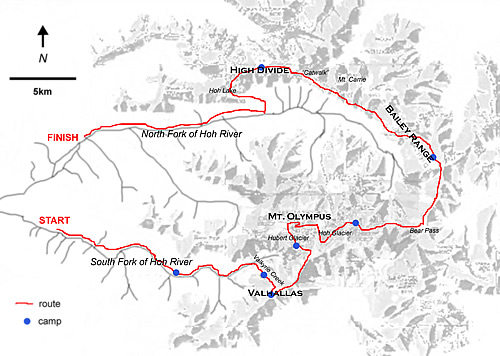

When planning the route, I had asked my parents for suggestions. Each destination my dad or mom suggested

sounded worthy but I had to choose just one. Or, did I? Where could I experience the essence of the Olympic

Mountains in one trip: The Valhallas, Mount Olympus, the Bailey Range, and the High Divide? I soon found

myself studying the map, entertaining a crazy thought of linking all of these destinations

into one giant high traverse.

So, with a sense of excitement over the prospect of new adventures and unseen vistas, I began

bushwhacking up the South Fork of the Hoh on July 5th. Joining me was a newfound friend Douglas from Port Townsend who,

despite his familiarity with the Olympic Mountains, had not set foot on any part of the obscure route we had chosen.

|

|

|

Parents of Steph Abegg in the Vallhallas in 1975. Barb Hemminger photo. Enlarge |

|

|

Day 1 – Bushwhacking up the South Fork of the Hoh

I’ve come to recognize the direct relationship between the difficulty of the first day and the worthiness of a

trip’s destination. Hence, with a sense of delight, Douglas and I attacked the thick tangle along the

South Fork of the Hoh.

We crawled over and under downed logs, beat our way through dense brush, and clung onto roots for dear life. Needless

to say, this was not easy with a 60-pound backpack! I suppose it was even less easy with the 60-pound external-frame

packs my parents carried back in the 70s. Sometimes we were on the wide flat area inside the river bends, allowing

for easier travel along sandbars and elk trails, but steep riverbanks and washouts would frequently force us to grunt

our way up and across brushy slopes. The tedium of the travel was broken by sunlight dancing on the river, or a moment

of wonder at the depth of the moss or the size of the trees. This valley, which straddles the park boundary, has never

been logged and four-foot-diameter giants of the forest are commonplace. Once we left behind the three miles of fisherman’s

trail, we found no sign of other humans until Mount Olympus.

My parents’ recollections indicate little has changed in the South Fork valley. My mom: “The bushwhacking was never-ending!

My legs got so scratched up, and several times I vowed never to hike without a trail again.” My dad: “It was a pretty hike

through the forest. Maybe slightly brushy at times, but at least the route-finding was easy."

We were slow going, but visions of the mysterious Valhallas spurred us onward. By dusk, we had traveled just over halfway to

Valkyrie Creek, which would be our line of access to the Valhallas. Finding a wide sandbar on an island, we spread our

sleeping pads under a comforting clear sky. We enjoyed hearty dinners – Douglas had Easy Mac and I had the first of my

tortilla wrap concoctions. We spent a few moments enjoying the stars before diving into our sleeping bags, Douglas using

his lightweight tarp tent as a comfy pillow, me using my tortillas.

|

|

|

Doug bushwhacking along the South Fork Hoh. Enlarge © Steph Abegg |

|

|

Day 2 – Bushwhacking Intensifies Along Valkyrie Creek

At some point the brush got so thick, the riverbanks so steep, and the packs so heavy, that the bushwhacking became an

absurd delight. The time went quickly, and by mid-afternoon we spotted Valkyrie Creek across the valley,

carrying snowmelt down from the Valhallas. The short description in the guidebook (Climber’s Guide to the Olympic Mountains,

by the Olympic Mountain Rescue Council) suggests crossing the South Fork about a half mile upstream of Valkyrie Creek and

ascending the 2,000-foot hillside east of the creek. So we continued upstream, searching for a safe way to cross the raging waters.

I had just devised a way we could use our climbing rope to cross when we spotted a giant tree spanning the river.

But crossing wasn’t that simple. We spent several minutes studying the colossal upturned wad of dirt and rotten roots we

would have to climb over to gain the trunk. With the rope we somehow got ourselves and our packs safely to the other side.

We wondered if any party had ever turned around here for lack of a viable tree crossing.

Later, I asked my parents how they had crossed. Whether they found a downed log or waded the river they cannot remember,

but they do recall heading for a shred of flagging tape on the south side of the South Fork. That flag, we learned, had marked

a sandbar where a Search and Rescue team had landed an evacuation helicopter a few weeks earlier. Mike Lonac was a pioneer

climber in the Olympic Mountains and especially the Valhallas, where he had several first ascents. In July 1980, in an

attempt to find a better access route, he was descending the steep forest next to Valkryie Creek when he slipped and fell

over a cliff band obscured by vegetation and died from his injuries. He had come for the fun and sport and had given his

life to it. My parents recalled the sobering moment of passing his abandoned backpack where the evacuation party had left

it. A paperback novel was still in the pack’s side pocket, and a tin Sierra cup inscribed “Lonac” perched on a nearby

bush, evidentially flung loose during the fall. In a sense, my parents completed his exploratory trip, which has since become

the most repeated line into the Valhallas.

Twenty-seven years later, Douglas and I stood on the south bank of the South Fork, staring up at the formidable forested slope.

It was 5 p.m., a reasonable time to call it quits and refresh our tired bodies by the cool river, but we had hoped to

finish the bushwhacking on the second day. Perhaps if we had been aware of the deadly history of the route’s next stage,

we would have waited to tackle the hillside in the morning. But we didn’t know, so we headed upwards into the steep forest,

naively hoping to reach alpine territory in a couple of hours.

|

|

|

Bed of lilies. Enlarge © Steph Abegg |

|

|

“I think we went too far to the left,” I mumbled as I found myself clinging desperately to a slippery moss-covered cliff.

It was easier to go up than down, but the higher we went the more dangerous a slip became. A slight shifting of the pack,

a particular placement of a stone, a bead of sweat on the fingers, and the South Fork of the Hoh would again have worn

flagging tape. Douglas recalled a foot slip that nearly sent him tumbling hundreds of feet to the river below before he

skated onto a well-placed ledge. But after several nerve-racking hours we left the moss-covered nightmare cliffs behind

and “aided” up slide alder with a clumsiness that would have been embarrassing anywhere else. We later agreed this was the

toughest part of the trip. I was beginning to understand why people don’t often go to the Valhallas.

We had just strapped on headlamps when we popped out onto a heather slope. The moment was one that words just

cannot describe, finally being free of the vertical brush and instead in a heather meadow tacked 2,000 feet above the river.

We spotted a small pool of melt water and a flat spot and were soon cocooned in our warm sleeping bags. As the brilliant

canopy of stars shone overhead, we felt glad to be alive and especially satisfied with our accomplishment for the day.

I couldn’t wait to see what adventures the next day would bring!

|

|

| Olympus Traverse |

Party:

Steph Abegg

Douglas Ray

|

|

| Itinerary |

|

July 5 – July 12

77 miles

July 5

Bushwhacking up the South Fork of the Hoh River. 8 miles.

July 6

More bushwhacking up the South Fork of the Hoh and a rather treacherous bushwhack up the hillside to the east of Valkyrie Creek. 9 miles.

July 7

Arrive at the Valhallas and ascent of Frigga (5,300 feet, Class 3) and Baldur (5,750 feet, Class 2). 3 miles.

July 8

Traverse from the Valhallas to the Hubert Glacier on Mount Olympus. 5 miles.

July 9

Ascending Mount Olympus (7,965 feet, Class 2 plus one pitch of 5.4). 9 miles.

July 10

Traversing to the southern end of the Bailey Range, and then the Bailey Range traverse to Mount Ferry. 11 miles.

July 11

Side-hill hiking the northern half of the Bailey Range to the High Divide. 13 miles.

July 12

Hiking the High Divide and the Hoh River trails.

19 miles

|

|

Steph's Laws of Backcountry Travel |

|

1. The coolest rock is always the heaviest and always found on the first day of the trip.

2. The brush is always thinner along the other side of the river.

3. The line of travel always lies along or over the edges of the map.

4. A jacket’s zipper will only get stuck when it begins to rain.

5. If you set up the tent, it won’t rain. If you don’t set it up, it will.

6. Wildlife only appear when your camera is put away.

7. Crampons and shoelaces will come undone at the worst possible moment.

8. The weather is always the nicest on the last day of the trip (although not true in our case, as we had only one day of rain out of eight). |

| |

| |

|

|